Guideline Paranoia

/By Carol Levy, PNN Columnist

I recently posted an article to an online chronic pain support group about the CDC’s opioid prescribing guideline.

“For treating acute pain, the guideline recommends a quantity no greater than what is needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids, specifying that three days or less will often be sufficient and more than seven days will rarely be needed,” the guideline states.

It makes sense to me. And I assumed that would be the response my post would get. The recommendation is only for treating acute pain and acute pain shouldn’t need chronic, long term opioid treatment.

Instead, the replies were quick, angry and knee jerk:

“How dare they decide what and how many we need? This will hurt chronic pain patients.”

“They always come after us. These may be for acute pain patients, but you just know more draconian guidelines are just around the corner for chronic pain patients.”

The CDC guideline does not say, “And no one, even if their acute pain continues longer than 3 or 7 days, will be able to get the pain meds they need.” But that was how it was interpreted.

And then the people replying went one step further: “Soon they will be writing guidelines that even those in chronic pain can only have opioids for a specified period of time and a specific dosage, and not one grain more or one day longer.”

I see this common response and reaction as a major issue. When any new guideline is proposed (and people forget these are guidelines, not absolutes), it is a major catastrophe: “They are coming after us.”

Too often we act in a way that appears akin to addictive behavior. We have to have our opioid medications. And any restriction, even when it is not related to chronic pain, is one restriction too many: “They are going to take away my drugs. Then what will I do?”

We seem to have lost the concept of consideration. No time is taken to think through the new suggestions. Instead it is an immediate jump to: “This will hurt me. I won't be able to get the meds I need.”

For many of us, opioid medication is all that is left or the only option. The idea that someone, especially the government, may rip them from us is truly terrifying.

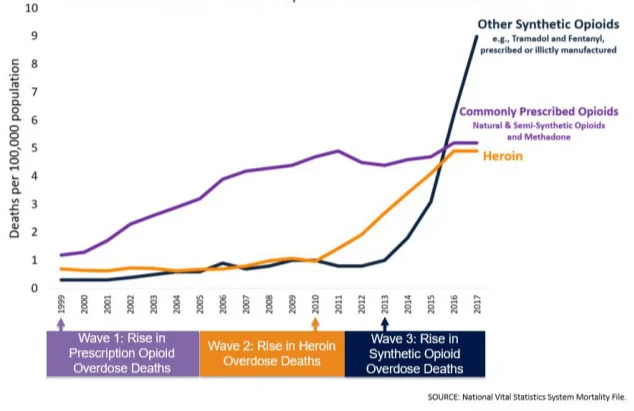

But I wonder. Maybe if we did not take any and all new guidelines as a frontal attack on us, maybe we would not be seen and referenced so often as a major component and cause of the “opioid epidemic.”

Carol Jay Levy has lived with trigeminal neuralgia, a chronic facial pain disorder, for over 30 years. She is the author of “A Pained Life, A Chronic Pain Journey.” Carol is the moderator of the Facebook support group “Women in Pain Awareness.” Her blog “The Pained Life” can be found here.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represent the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.