10 Ways To Survive Home Isolation

/By Barby Ingle, PNN Columnist

On November 2nd last year, I fell very ill. It was a Saturday evening. I was fine and then I was having trouble breathing. Two days later I was diagnosed with pneumonia and on the 18th I was told that I had Valley Fever.

My immune system is already weak due to multiple chronic conditions, and catching any kind of acute cold or flu is life-threatening for me. I was put on a breathing machine, which was new for me, and advised to stay home to avoid further infections.

Being homebound is something I have been doing for a very long time. By the time Covid-19 struck and a push for social and physical distancing began, I had already been isolated for years and ultra-isolated since November. I still have Valley Fever symptoms, which are similar to coronavirus, and still have a mass on my upper right lung. I have tested negative for both Covid-19 and its antibodies.

Now that being physically isolated is a thing, many are asking me for advice on what to do or how to make it through self-quarantine. Spending so much time at home, I’ve found that I have a lot of energy and have to turn to other activities to keep my spirits up. These are what I’ve come up with.

Catch up on reading: Not everyone is ready to write a book, but reading one is something most of us can do. Expand your mind and educational knowledge by reading about subjects that have interested you and would like to learn more about.

Dance party for one: It doesn’t matter if you can dance or not, no one is watching! Just put on some music and move your body. Movement can help circulate blood, increase endorphins and improve your mood. I always love a good spontaneous dance party!

Games on your phone: For this you need a smart phone. My personal games are the free apps that keep my mind working. I like Solitaire, Drop the Number, Pull the Pin and Woodoku.

Netflix: I never saw the need for Netflix until I had it. When people reached out and asked what they could do to help, this was one of the tools someone set us up with. We have watched more TV shows in the last 9 months than the previous 5 years. Everything from great dramas like Ozark and The 100, to comedies like You’re Dead To Me, Shameless and Happy! I’ve also enjoyed reality shows such as 100 Humans, Alone and Naked and Afraid.

Organize your medical records: For those of you who have thick case file like me, what better time to order and organize your medical records? You can also address any mistakes in those records and be better prepared for future care by staying organized.

Social media: We may be physically distant, but socially we can still be engaged. When I am up to it, I post updates. I’ve also been sharing messages and articles a lot more since I am not creating as much content during this period. I believe my followers like it and I know the people I share appreciate it as well.

Start a gratitude journal: Isolation can lead to negative feelings, such as being scared, anxious, mad and sad. This can have an impact on you and your loved ones. Taking the time to write a gratitude list of the positive things in your life and the things you can still do (even if it is just taking a shower) can be a good tool for keeping a positive attitude. A gratitude journal can also be something you look back on to help see all the good in your life, even in the toughest of times.

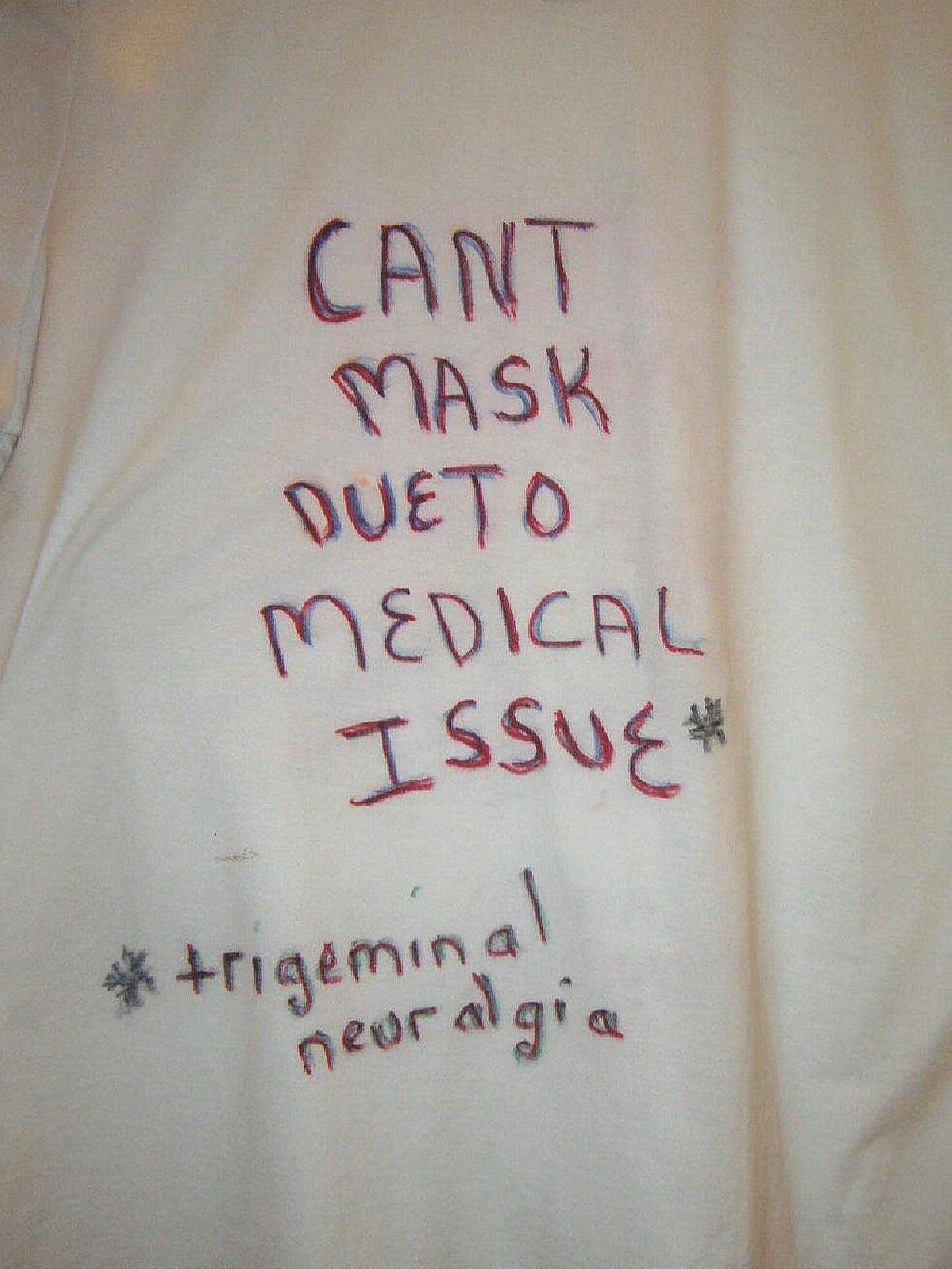

Start a new project: You could learn a new hobby, craft or language, or develop your appreciation for art. They say 21 days of something will improve your skills. When will you ever have this much time to do something, even if it is just a little each day?

Interview family members: With the passing of all of my grandparents and parents in recent years, I wished I had done a legacy video with each of them. I asked my mother-in-law do an interview with me and turned it into a Christmas present for both of her boys and our nephews. It’s a great way to get a living picture that is enduring, long past the time we are here on earth. It also gives us more social contact with the older members of the family.

Rest! This one is the best for me. Because of how tired I am, I give myself permission to rest as much as possible and get nothing much done. My days are filled with resting and relaxing most of the time. There is no pressure or stress to do it any other way.

Do you have other ideas on how to survive isolation and stay engaged with the world? Please share your thoughts in the comment section below.

Barby Ingle lives with reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), migralepsy and endometriosis. Barby is a chronic pain educator, patient advocate, and president of the International Pain Foundation. She is also a motivational speaker and best-selling author on pain topics. More information about Barby can be found at her website.