Long COVID Risk Declining, Mostly Due to Vaccinations

/By Crystal Lindell

Rates of Long Covid appear to have declined over the course of the pandemic, according to new research from the Washington University School of Medicine. One reason is that people who are vaccinated against COVID-19 and its variants have about half the risk of developing Long Covid than those who are unvaccinated.

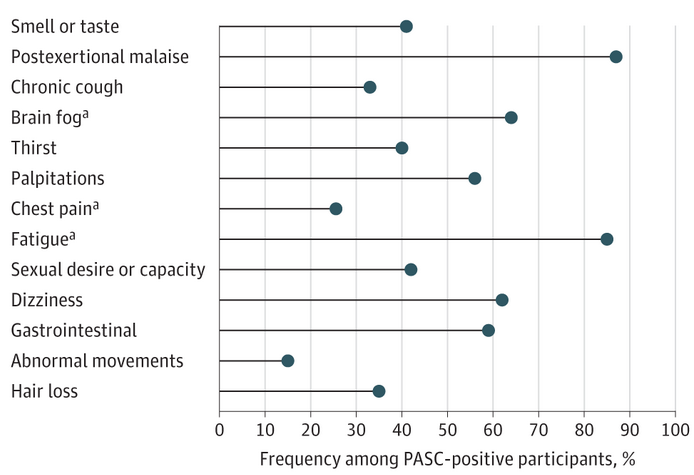

Long Covid refers to a wide range of symptoms that some people experience four or more weeks after an initial infection with COVID-19. Symptoms such as fatigue, body pain and shortness of breath may last for weeks, months or years, and can be mild or severe.

While the new research only looked at COVID cases through 2022 – making it unclear how newer COVID strains and vaccines in 2023 and 2024 may be impacting Long COVID cases – it does provide a ray of hope.

Specifically, researchers attributed about 70% of the risk reduction to vaccination against COVID-19 and 30% to changes over time, such as the evolving characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and improved detection and management of COVID-19. The research was published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“The research on declining rates of long COVID marks the rare occasion when I have good news to report regarding this virus,” said the study’s senior author, Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, a Washington University clinical epidemiologist and global leader in COVID-19 research. “The findings also show the positive effects of getting vaccinated.”

Although the latest findings sound more reassuring than previous studies, Al-Aly tempered the good news.

“Long COVID is not over,” said the nephrologist, who treats patients at the John J. Cochran Veterans Hospital in St. Louis. “We cannot let our guard down. This includes getting annual COVID vaccinations, because they are the key to suppressing long COVID risk. If we abandon vaccinations, the risk is likely to increase.”

For the research, Al-Aly and his team analyzed millions of de-identified medical records in a database maintained by the Department of Veterans Affairs, the nation’s largest integrated health-care system.

The study included over 440,000 veterans with SARS-CoV-2 infections and more than 4.7 million uninfected veterans. Patients included those who were infected by the original strain, as well as those infected by the delta and omicron variants. Some were vaccinated, while others were unvaccinated.

The Long COVID rate was highest among those with the original strain, about one in every ten (10.4%). No vaccines existed while the original strain circulated.

The rate declined to 9.5% among those in the unvaccinated groups during the delta era and 7.7% during omicron. Among the vaccinated, the rate of Long COVID during delta was 5.3% and 3.5% during omicron.

“You can see a clear and significant difference in risk during the delta and omicron eras between the vaccinated and unvaccinated,” said Al-Aly. “So, if people think COVID is no big deal and decide to forgo vaccinations, they’re essentially doubling their risk of developing long COVID.”

Al-Aly also emphasized that even with the overall decline, the lowest rate — 3.5% — remains a substantial risk.

“That’s three to four vaccinated individuals out of 100 getting long COVID,” he said. “Multiplied by the large numbers of people who continue to get infected and reinfected, it’s a lot of people. This remaining risk is not trivial. It will continue to add to an already staggering health problem facing people across the world.”

The World Health Organization has documented more than 775 million cases of COVID-19.

Disabled at Higher Risk of Long COVID

The CDC recently found that Long COVID symptoms were more prevalent among people with disabilities (10.8%) than among those without disabilities (6.6%).

The new data was released as part of the CDC’s annual update to its Disability and Health Data System, which provides quick and easy online access to state-level health data on adults with disabilities.

The report found data that over 70 million adults in the U.S. reported having a disability in 2022.

Older adults reported a higher disability rate (43.9% for those aged 65 and older) compared to younger age groups. The race/ethnic groups with the highest rate of disability, regardless of age, identified as American Indian or Alaska Natives.

The CDC has fact sheets that provide an overview of disability in each state, including the percentages and characteristics of adults with and without disabilities. Click on any state listed here to view that state’s profile.

The findings underscore the fact that people with disabilities are a large part of every community and population.