By Dr. Lynn Webster, PNN Columnist

I am a beneficiary of white privilege. That doesn't mean I was born into money. On the contrary, I grew up in a poor, uneducated family in a rural community. I felt the world looked down on my family because of our socio-economic circumstances.

As a child, I feared I would never escape poverty or its stigma. The system seemed to favor those with money and education. Yet I was able to climb out of poverty because of a supportive family.

In retrospect, I believe the opportunities that opened up to me were due to more than family support. Although I had good grades in college, my acceptance to medical school may have been due, in part, to where I grew up.

The medical school to which I applied hoped to increase the number of family physicians willing to set up practices in rural communities. Their strategy was to choose students who had grown up in rural areas, assuming they would be likely to return to those communities to practice medicine.

I was never aware of a similar strategy for enticing doctors to practice in inner city or other predominately African American communities. There were no African Americans in my class of 120.

Shortly before entering medical school, I was in a serious car accident. I rolled my car during a thunderstorm on the highway from Lincoln to Omaha, Nebraska. The seat belt I was wearing saved my life, but in doing so, it produced a compression fracture of a lumbar vertebra. I was in excruciating pain until the emergency room physician gave me morphine.

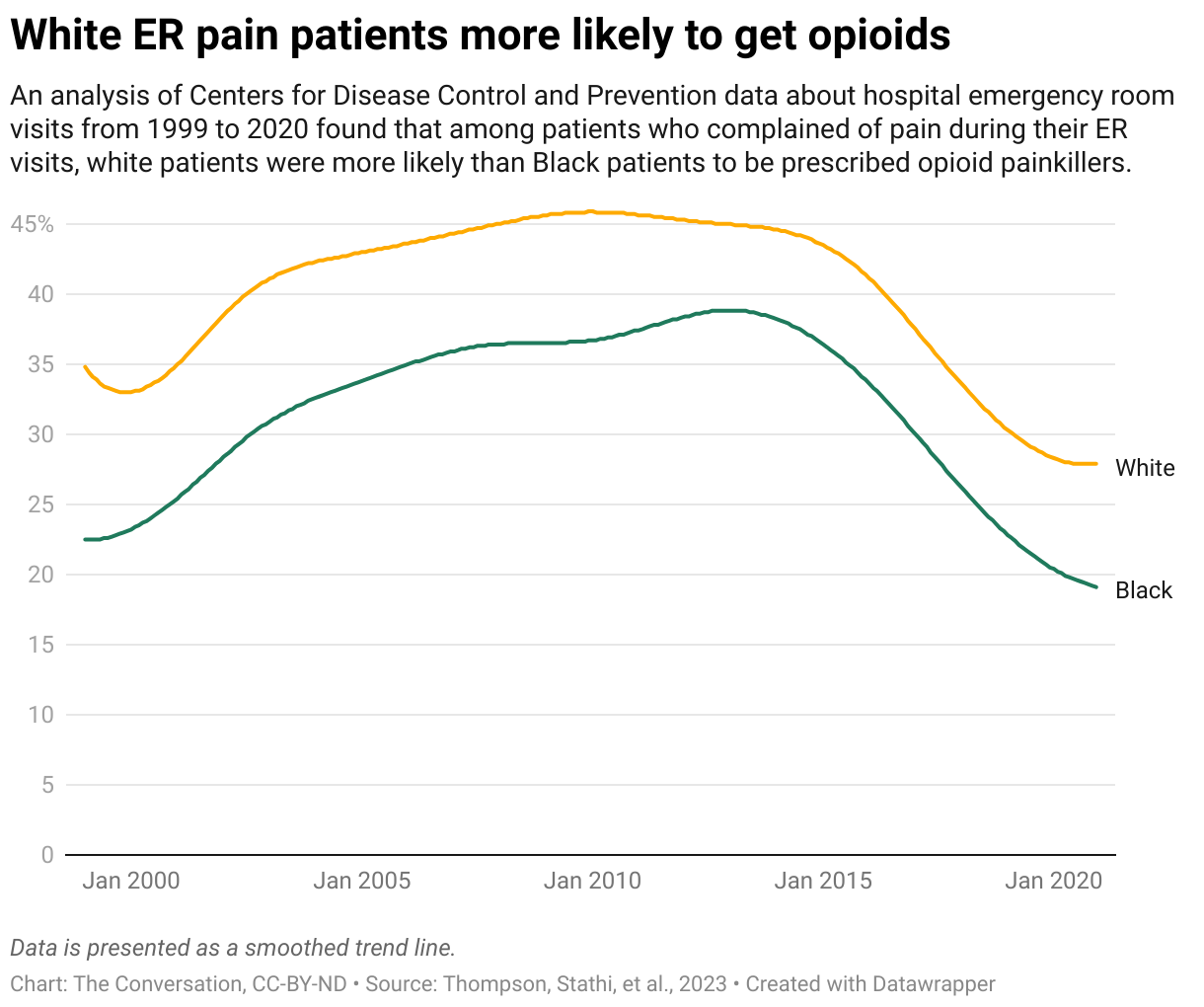

If I had been of a different race, would I have been treated with the same compassion? Research today suggests I probably would not have been.

Myths About Black People and Pain

For centuries, there has been a false belief that blacks could tolerate more pain than whites. In 1851, a prominent southern physician wrote in the New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal that due to “physical peculiarities of the Negro race,” black slaves were “insensitive to pain when subject to punishment.”

Even today, a young black man who goes to the emergency room with an injury is likely to be treated differently than a young white man. For example, a 2000 Annals of Emergency Medicine article reported that in an Atlanta emergency department, 74% of white patients with bone fractures received an opioid, but only 57% of African American patients with the same condition received the same treatment.

A 2016 study in The Proceedings National Academy of Sciences reported that a significant number of University of Virginia medical students believed there was a biological difference in pain perception between blacks and whites. The study exposed myths such as the common belief that "black people’s nerve endings are less sensitive than white people’s." In fact, 40% of first- and second-year medical students in the study agreed with the statement, "Black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s."

Another way of expressing the same opinion is to say that whites are more sensitive to pain than blacks. These myths are embedded in American culture and have been fomented by institutional racism.

A more recent study found that black children with appendicitis were less likely to be prescribed an opioid for their pain than white children.

Since blacks who are in pain are regarded with greater suspicion than whites, they tend to underplay the intensity of their pain in clinical settings. They are also more inclined than their white counterparts to try to pray their pain away or to consider pain to be a personal failing.

Despite common folklore, African Americans and Hispanics are less likely than white people to abuse prescription opioids. Yet blacks of all ages usually receive less pain medication than their white counterparts. They wait longer in emergency rooms for painkillers and receive less effective pain management when in hospice care.

The disturbing belief that blacks are more tolerant of pain is a form of racism. However, ER doctors who discriminate against blacks may not be racists. Their behavior, instead, may be due to the systemic racism in our culture. The difference is this: A racist acts upon an intent to discriminate based on race or ethnicity. Racism, on the other hand, is when actions are based upon false beliefs.

As Cory Collins writes in Teaching Tolerance, "Having white privilege and recognizing it is not racist."

Racism Isn't Over

On November 4, 2008, Barack Obama was elected as the first African American president of the United States. He said, at the time, "Change has come to America," and many Americans wanted to believe it had. Many hoped the election signaled that, finally, Americans perceived blacks as equal to whites, and racists had lost their influence in this country.

However, according to the Pew Research Center, Americans’ views of racist behavior have become polarized along party and racial lines. In 2019, about 58% of all Americans believed that race relations were bad and unlikely to improve. Then came the killing of George Floyd and the subsequent protests about the racial disparity demonstrated by law enforcement.

Increased awareness of the pervasiveness of institutional racism throughout our culture may be growing, but racism is certainly not over. Research clearly shows that racism, unconscious or not, keeps people of color from getting the pain treatment they need and deserve. White medical students and health care professionals must recognize the role white privilege plays in passive but brutal discriminatory practices, and actively work to rectify and remedy them.

Lynn R. Webster, MD, is a vice president of scientific affairs for PRA Health Sciences and consults with the pharmaceutical industry. He is author of the award-winning book, “The Painful Truth,” and co-producer of the documentary, “It Hurts Until You Die.” You can find Lynn on Twitter: @LynnRWebsterMD