A History Lesson of the War on Drugs

/By Iris Erlingsdottir, Guest Columnist

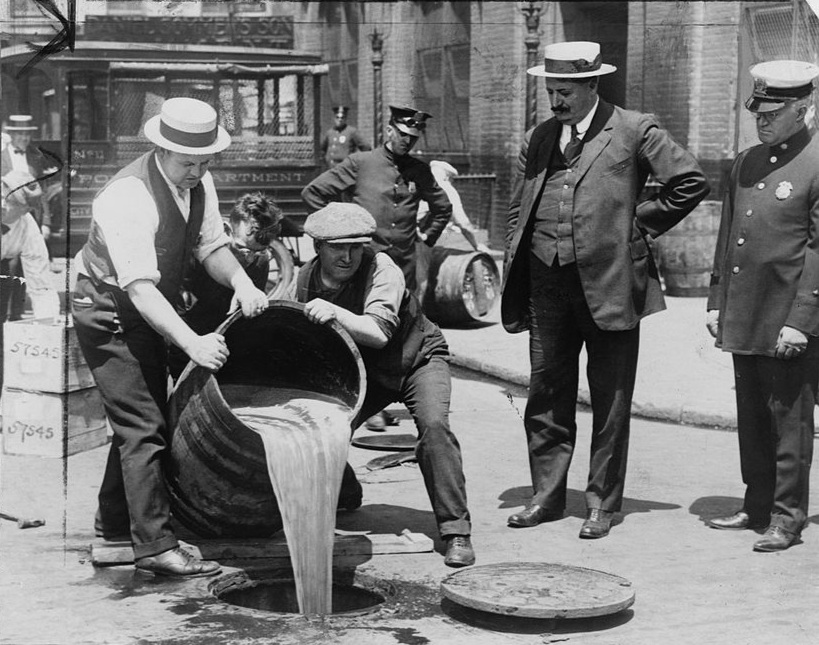

One hundred years ago this month, the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, prohibiting the production, transport and sale of "intoxicating liquors.” It cleared the way for the Volstead Act, which declared that liquor, wine and beer all qualified as intoxicating liquors.

Prohibition – the first War on Drugs -- was on.

The U.S. government has never been above abusing its citizens in the name of fighting drug wars. Then, like now, government efforts to legislate the human condition were a losing, deadly battle. In today’s war against opioid addiction, it is patients on the receiving end. A century ago it was drinkers.

Alcohol deaths only increased during Prohibition, as Deborah Blum recounts in her 2010 book, “The Poisoner’s Handbook.”

Policymakers believed poisoning the alcohol supply was an acceptable way to stop people from drinking. Methanol was added to industrial alcohol to make it unfit for human consumption, but bootleggers found ways to distill the poisoned alcohol to make it drinkable.

The government responded by adding even more toxic chemicals, like gasoline and kerosene. And bootleggers kept stealing the increasingly dangerous alcohol and turning it into liquor.

At the start of Prohibition, New York City’s Bellevue Hospital treated about twelve annual cases of moonshine and wood alcohol poisoning. About a fourth of those were fatal. By 1926, the hospital treated 716 people for blindness and paralysis due to poisoned alcohol. The holiday season that year was especially deadly. On Christmas Day alone, 60 people were treated at Bellevue for alcohol poisoning and eight died from it. By New Year’s Day 1927, 41 people were dead.

Prohibition-era statistics are notoriously unreliable, but according to some estimates over 10,000 Americans died during Prohibition from the effects of drinking poisoned liquor, courtesy of both government and organized crime chemists. Many more were blinded. Prohibition’s attempt to foster temperance instead fostered intemperance, along with violence and crime. The solution the government had concocted to address alcohol abuse had made the problem worse.

Act of Betrayal

“There is no Prohibition,” New York City medical examiner Charles Norris said in an angry report about the alcohol deaths. “All the people who drank before Prohibition are drinking now — provided they’re still alive.”

Norris and his staff considered the government’s deliberate poisoning of alcohol an “act of betrayal.” They weren’t accustomed to having their national government adopt a policy known to kill people.

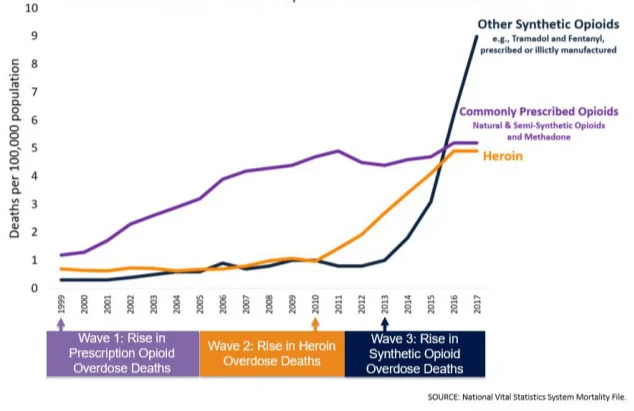

Policymakers in the 21st century have few such qualms about the opioid crisis. Nor does the media, which continues to parrot the government’s blatantly misleading propaganda, blaming illicit fentanyl and heroin deaths on prescription opioids. Just as thousands died from alcohol poisoning during Prohibition, opioid hysteria has had horrible consequences for millions of patients doomed to suffer torturous pain because of irresponsible journalism and the policy blunders it enables.

Many of the nation’s largest Prohibition-era newspapers, however, didn’t hesitate to condemn a government policy “gone haywire.”

“Prohibition in this area is a complete failure,” the New York Herald Tribune’s editorial page declared, “enforcement a travesty, the public a victim of poisonous liquor.” The Evening World said no administration had been more successful in “undermining the health of its own people,” while The St. Paul Pioneer Press called the government an “accessory to murder.”

Perhaps the Chicago Tribune stated it best: “It is only in the curious fanaticism of Prohibition that any means, however barbarous, are considered justified.”

It’s a sentiment that applies just as aptly to today’s epidemic of opioid hysteria.

Íris Erlingsdóttir is an Icelandic journalist and writer who lives in Minnesota. Iris has a rare, untreatable arthritic condition that causes severe pain and progressive destruction of the joints. She became an advocate for pain patients’ rights after being denied continued opioid pain medication.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.