Living with a Beast

/By Cathy Kean, Guest Columnist

I am living with a beast who is cold, heartless, unmerciful, uncaring and cruel. Always lurking around me, making my life so challenging, so exhausting, and so painful. Not only physically, but mentally, spiritually and emotionally.

This beast has taken so much from me, I hardly remember how it was before it came into my life. Of course, I had challenges and difficult times. But I was functional and happy. And I could cope! I could manage!

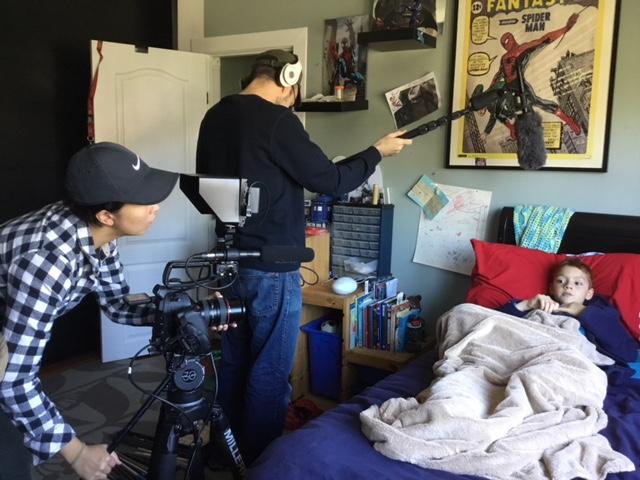

Now I have had to deal with this evil and vindictive beast. I live day in and day out in my cave (my bedroom), lying in bed. I rarely venture out anymore. I've become isolated and alone; so different from the life I used to live.

I wish that I had swallowed and drunk up and absorbed the greatness and beauty of the life I had before, and not taken it for granted. What I wouldn't do or give to go back to that time!

I mourn me. I miss me. I know my kids and my grandchildren miss me. The woman I used to be was energetic, vivacious, outgoing, industrious, loving and friendly. There wasn't a person that could walk by me without me engaging in some kind of banter. I loved life so much more then!

Now I am attacked when I least expect it. I have no way of knowing how or when, because the beast is always present, always lurking around. It has hurt my family, my career, my outlook and my sense of self. I am followed everywhere.

When the beast is angry, my days are hell and my nights sleepless. It is behind me, beside me, everywhere, every day. I truly cannot remember a time that I lived totally out of its grasp.

This fiend’s name is PAIN.

Pain is brutal, savage and barbaric at times. Pain cares little for family occasions, social events or holidays. Pain forces me to stay home, ensuring I don’t forget its brute presence for a second. The beast has been a silent witness to some of the most extraordinary and excruciatingly painful moments of my life.

There are so many who live with this insidious beast, just like I do. We do our best to keep on living, despite pain's germinating presence. You never become immune to the torturous, aching, stabbing, aching and suffering that pain brings, regardless of how long you live with it.

I am trying to learn that this is my new normal and I must continue with my life. I try to smile, laugh and engage, despite the struggle, strain and toil it causes. But I feel like I have been robbed!

I need to tell those who do not have chronic pain a little secret.

It hurts all day, every day, 24/7.

365 days a year.

It never stops.

It never ends.

You eat, it hurts.

You sleep, it hurts.

You just exist, it hurts.

You rest, it hurts.

You breathe, it hurts.

Every single aspect of every single day, it hurts.

And now without my essential tools (my medications) that gave me functionality, my quality of life has diminished 98% due to CDC guidelines. I truly don't know how much longer I can stay in this fight, this madness, this torment and this torture.

Constant and chronic pain isn’t something you can deal with for a long period of time. My organs are starting to shut down. I am blacking out constantly. I am having cardiac issues. I am in so much pain, I pray to God to take me!

I have begged my adult children to please not be angry with me if I take my life. I want to be here! I want to see my grandbabies grow up. I want to engage in life again!

I made a difference in peoples’ lives. I used to be a parent's last hope for true help and success when I had access to my medications. I was a special education advocate and I was good! I knew those feelings of desperation, not knowing where to turn or what to do for your child.

I just wish the government, our families, friends, and society would see us as human beings with value. Please be more compassionate, more loving and more accepting of our limitations.

No one would ask or want to live with this beast, this madness! I promise you!

Cathy Kean lives in California. She is a grandmother of 7 and mother of 4, who has chronic pain from lupus, fibromyalgia, Parkinson's disease, and stiff person syndrome. Cathy is a proud member of the Facebook group Chronic Illness Awareness and Advocacy Coalition.

Pain News Network invites other readers to share their stories with us. Send them to editor@painnewsnetwork.org.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.