How I Learned to Handle Chronic Pain

/By Emily Ullrich, Columnist

It occurred to me the other day that I’ve come a long way since my initial chronic illness set in. It has been a rough journey, but overall, I feel myself to be “improved.”

I have more self-esteem. I am more positive emotionally and spiritually. And I am far better at handling my multitude of symptoms than I was.

I went through complete and utter Hell, but came out of it, and I think it is really important for people who are new to chronic pain and for those who are really struggling to know that it will get better.

Let me be clear. I am not saying, “Don’t worry, it’ll all straighten itself out and you’ll be back to your old self in no time.” I am absolutely not saying that. But, I am saying if you work, learn, and lean into it, it will get better—at least you will get better at handling it.

I think every so often it is important to assess yourself, your goals, your progress, your changes, your heart, where you are, and where you need to go. When you develop chronic pain, these goals and dreams have to be adjusted.

In 2011, I returned to the United States a shell of a woman. My overly ambitious goal to start a film school and a new life in Kenya had not worked out the way I had imagined. Worst of all, I kept getting sick, and finally I had to put my tail between my legs and go home to momma, in Kentucky.

I woke up on my very first morning back on American soil screaming in pain. I had a kidney stone. It was some kind of divine intervention that this pain held off over the 25 hour flight, and the days before I left Kenya, because there’s no way I could have handled it or found help.

EMILY UlLRICH

This was just the beginning of a slew of chronic illnesses, diagnoses, misdiagnoses, doctor and hospital visits -- so many that they flow into one another and overlap in my mind -- and an ambush of tumultuous emotions, all of which would be a nightmare for me and my poor mother, for the next three years or so.

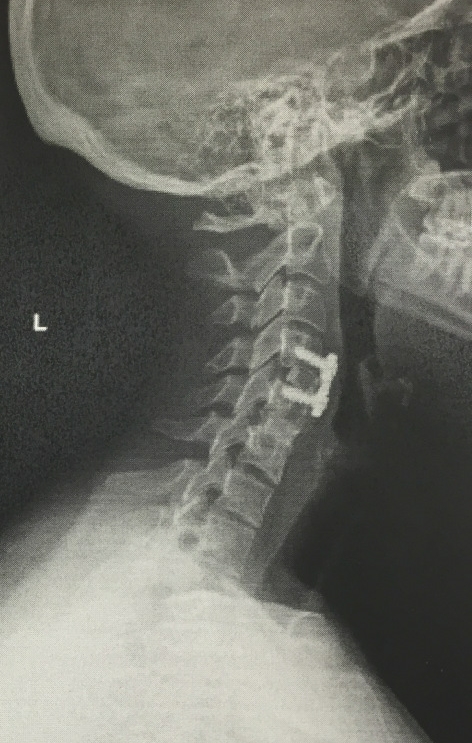

From the time the kidney stone stirred a commotion in my body, the pain changed, and it never really went away. It became chronic pelvic pain, then fibromyalgia, migraines, and a flare up of malaria returned after I had one of many endometriosis surgeries.

At the time, I did not have health insurance, and in Kentucky, a single woman without children could not get Medicaid. The main suggestion for my condition was the Lupron shot, which cost $700 over the internet through a Canadian pharmacy, the only possible way I could afford it.

It would put me into early menopause, which I really did not want. The shot would only last six months, and then I would have to come up with another solution.

All of this was overwhelming. Worst of all, I had to see about 15 gynecologists and make endless ER visits with uncontrolled pain, before finally someone suggested a pelvic pain specialist to me. He was the first person to tell me that this was not normal. Most every doctor before him had told me it was normal to have some degree of “female pain.”

In the days and months that passed, I tried to hold onto my job as a professor in Cincinnati, which was not a short commute. I was put on so many different medications (hormones, steroids, tricyclic antidepressants, fibro medications, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, pain meds, NSAIDs, the list goes on) that I found out the hard way that I am allergic to a lot of them!

My own doctor told me to lie to the government and say I was pregnant, so I could get Medicaid, and then say I had a miscarriage and get the Lupron shot. He also told me it was time to stop working. I cried to him. I cried to my mother. I cried to myself.

Meanwhile, I was having so many different reactions from the medications, I would be up all night, muscles twitching, grinding my teeth, restless legs kicking out of control. Every day, I woke up expecting to feel better, only to be disappointed. I would be so tired I could sleep for days. My entire body and mind were highly agitated to the extreme.

I did not yet grasp the concept of chronic. I knew the word by definition, but had no idea what it meant as it applied to my life.

Now, after endless doctor visits and hospitalizations, I am doing better. I am not better physically, in fact I have FAR more problems and diagnoses than I did. But, I’ve become a medical research specialist, and have been lucky enough to be affiliated with numerous pain organizations, support and information groups. I’ve started speaking out and advocating, which gives me strength. I’ve married a kind, supportive, understanding, empathetic, and wonderful man.

I have a handful of doctors I trust, and one -- my pain doctor, who I’ve only been with for a few months -- is an absolute angel who actually cares about my pain.

I am a work in progress, but I know I am making progress, and that’s what counts.

Emily Ullrich suffers from Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction, Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, endometriosis, Interstitial Cystitis, migraines, fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, anxiety, insomnia, bursitis, depression, multiple chemical sensitivity, and chronic pancreatitis

Emily is a writer, artist, filmmaker, and has even been an occasional stand-up comedian. She now focuses on patient advocacy for the International Pain Foundation, as she is able.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.