Feds Urge Doctors to Co-Prescribe Naloxone

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

Pain patients taking relatively modest doses of opioid medication should be co-prescribed naloxone, according to a recommendation released this week by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

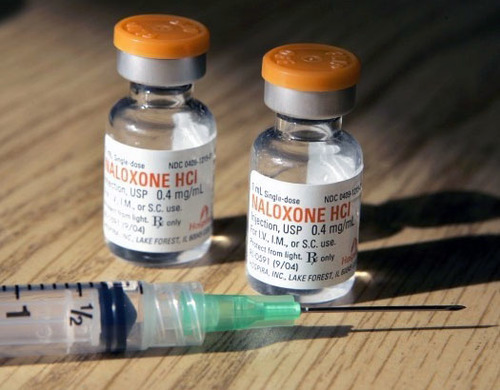

Naloxone is an overdose recovery drug administered by injection or nasal spray that rapidly reverses the effects of an opioid overdose. It has been credited with saving thousands of lives, although recently there has been controversy over a company exploiting demand for the drug by raising the cost of its naloxone injector over 600 percent.

“Given the scope of the opioid crisis, it’s critically important that healthcare providers and patients discuss the risks of opioids and how naloxone should be used in the event of an overdose,” said Adm. Brett Giroir, MD, assistant secretary for health and senior advisor for opioid policy at HHS.

“Co-prescribing naloxone when a patient is considered to be at high risk of an overdose, is an essential element of our national effort to reduce overdose deaths and should be practiced widely.”

But the “guidance” released by HHS could involve millions of patients who are not necessarily at high risk and have been taking opioids safely for years. It urges doctors to “strongly consider” prescribing naloxone to patients under these circumstances:

Patients prescribed opioids at a dose of 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) or more per day

Have respiratory conditions or obstructive sleep apnea (regardless of opioid dose)

Have been prescribed benzodiazepines (regardless of opioid dose)

Have a mental health or non-opioid substance use disorder such as excessive alcohol use

Are receiving treatment for opioid use disorder

Have a history of illegal drug use or prescription opioid misuse

The HHS guidance was issued days after an FDA advisory committee voted 12 to 11 in favor of adding language to opioid warning labels recommending that naloxone be co-prescribed. Some panel members objected to the labeling because of the additional cost involved and because it does not address deaths caused by illicit opioids, which account for the vast majority of opioid overdoses.

The guidance notes that most health insurance plans, including Medicare and Medicaid, will cover at least one form of naloxone. For patients without insurance, the guidance suggests contacting a state or local program that may supply naloxone for free or at low cost.

Naloxone costs only pennies to make and syringes containing generic versions of the drug typically cost about $15 each. But formulated and branded versions that have a more sophisticated delivery system are much pricier. According to Health Care Bluebook, a package of two nasal sprays of naloxone sold under the brand name Narcan will cost about $135. Evzio, a kit that contains two auto-injectors of naloxone, retails for about $3,700.

A recent U.S. Senate report found that Kaleo, a privately-owned drug maker, jacked up the price of Evzio by over 600% to “capitalize on the opportunity” of a “well established public health crisis.” As a result, the report estimates the U.S. government paid over $142 million in excess costs to Kaleo for prescriptions covered by Medicare.

The new HHS guidance mirrors that of the 2016 CDC opioid guideline, which encourages physicians to consider prescribing naloxone to pain patients on “higher opioid dosages” of 50 MME or more.

“I’m personally against it, because I don’t think most patients who require opioids for pain management are at risk of overdose,” said Andrea Anderson, Executive Director, Alliance for the Treatment of Intractable Pain (ATIP). “I also don’t think naloxone helps unless you’re with other people, which makes more sense for those who are using illicit opioids rather than those who rely on opioids for routine pain relief.

“I don’t think the government should require patients to buy medications for which they do not have a proven need. This sounds like another one of those good ideas in theory but poor in practice.”