Opioid Prescribing Falls in Canada, But Are Patients Better Off?

/By Pat Anson

The number of patients prescribed opioids for pain in Canada has fallen over 11% in recent years, according to a new study published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ). The decline reflects trends in the U.S. and other Western nations, which adopted stronger guidelines to discourage opioid prescribing nearly a decade ago.

Like most studies of its kind, the new research only looked at the number of opioid prescriptions that were dispensed, and did not evaluate the health or quality of life of Canadian patients after access to opioids was reduced, or whether their pain improved using non-opioid pain therapies.

In 2022, about 1.8 million Canadians began taking an opioid to manage pain for the first time, 8% less than when the study period began in 2018.

“Our study provides valuable information on the progressive decline of prescription opioid dispensing for pain and high-dose initiations among new users, as well as the types of opioids prescribed and important geographic differences in these trends across Canada,” wrote lead author Nevena Rebić, PhD, a clinical researcher at Unity Health Toronto.

“Our findings suggest that national efforts to promote opioid stewardship and safer opioid prescribing for acute and chronic noncancer pain over the past decade have had an impact.”

“High-dose initiations” were defined as daily dosages that are above Canada’s recommended dose of 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) or lower. Less than 20% of new prescriptions in Canada exceeded 50 MME. Over half of the opioid prescriptions were for codeine.

Patients most likely to be prescribed an opioid were females, older adults, rural residents, and those living in lower-income areas.

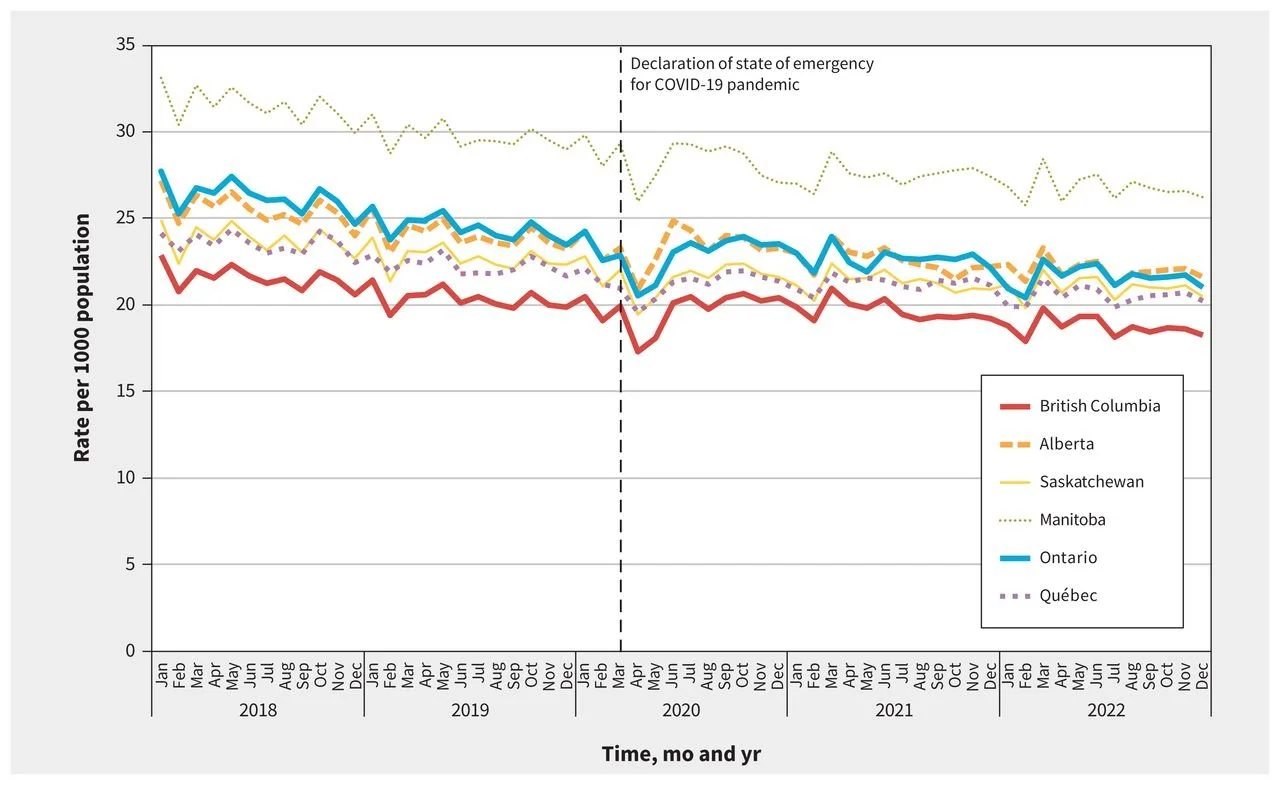

Manitoba consistently had the highest rate of opioid prescribing, while British Columbia had the lowest among the six provinces that were studied. The lower rate in BC is somewhat surprising, given the province’s reputation as the being the epicenter of the “opioid crisis” in Canada.

Monthly Rate of Opioid Prescribing in 6 Canadian Provinces

SOURCE: CMAJ

Rebić and her colleagues cautioned that “ongoing monitoring is needed” to ensure that pain patients are not left suffering from inadequate pain management, rapid opioid tapering or discontinuation, or that they turn to street drugs for relief. The authors acknowledge that has occurred “in some cases,” without exploring the severity of the problem.

“If the (opioid) pain prescribing is better, then why do we still get letters from patients in extreme pain telling us they were cut off, tapered or refused medical care?” asks Marvin Ross of the Chronic Pain Association of Canada (CPAC), which has long criticized Health Canada and the authors of Canada’s medical guidelines for discouraging the use of opioids.

Ross said the new analysis of opioid prescriptions was “a waste of time, money and effort,” and called the researchers “inane pill counters” who lack clinical experience with patients.

“The purpose of prescribing a pill is to help the patient get better or to ameliorate their symptoms, so saying we prescribed 10% fewer pills tells you nothing about that. To focus on the number says nothing about achieving prescribing goals unless you begin from the bias that prescribing any of it is bad,” Ross told PNN in an email.

In a commentary on the study also published in CMAJ, an anti-opioid activist claimed that addiction and other potential harms of opioids are being overlooked by Canadian doctors who still prescribe them too freely.

“Most clinicians have seen first-hand how well opioids can work when first given. But they are at their pharmacologic best in the initial days of treatment. Continue them for weeks, months, or years and the calculus becomes progressively less favourable,” wrote David Juurlink, MD, a clinical internist at Sunnybrook Research Institute, and a member of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP).

“In this way, opioids transition from effective analgesics to drugs required primarily to stave off a withdrawal syndrome they themselves created.”

According to a recent analysis by Health Canada, only 18% of fatal opioid overdoses in Canada in early 2025 involved a pharmaceutical opioid. The vast majority of deaths were linked to illicit fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, and other illicit opioids such as heroin.