U.S. Overdose Crisis Could Be Worse Than We Thought

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

The number of deaths attributed to opioid overdoses in the U.S. could be 28 percent higher than reported due to incomplete death records, according to a new study appearing in the journal Addiction. Researchers at the University of Rochester say nearly 100,000 overdose deaths may not have been counted because the opioid involved was not identified.

The discrepancy is pronounced in several states, such as Pennsylvania, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Indiana, where the actual number of overdoses caused by legal and illicit opioids could be twice as high as current estimates.

"A substantial share of fatal drug overdoses is missing information on specific drug involvement, leading to underreporting of opioid-related death rates and a misrepresentation of the extent of the opioid crisis," said senior author Elaine Hill, PhD, an economist and assistant professor in the University of Rochester Medical Center. "The corrected estimates of opioid-related deaths in this study are not trivial and show that the human toll has been substantially higher than reported, by several thousand lives taken each year."

Hill and her colleagues found that almost 72 percent of unclassified drug overdoses that occurred between 1999 and 2016 involved prescription opioids, heroin or illicit fentanyl — translating into 99,160 additional opioid-related deaths.

Researchers discovered the discrepancy while studying the economic, environmental and health impact of coal mining and oil and gas drilling. Appalachia and other regions of the country hit hardest by the opioid crisis overlap with areas where there is coal mining and shale gas development.

As a part of her research, Hill was attempting to determine whether the shale boom improved or exacerbated the opioid crisis. She discovered that close to 22 percent of all drug-related overdoses were unclassified, meaning the drugs involved in the cause of death were not reported.

A 2018 study at the University of Pittsburgh reached a similar conclusion, estimating that as many as 70,000 opioid related-deaths were not reported. Coroners and medical examiners in many states often did not specify the drug that contributed to the cause of death.

Critics have long complained that overdose data reported by the CDC and other federal agencies is flawed or cherry-picked. CDC researchers admitted in 2018 that deaths attributed to opioid medications were “significantly inflated” because overdoses involving illicit fentanyl were erroneously counted as prescription opioid deaths. Toxicology tests cannot distinguish between pharmaceutical fentanyl and illicit fentanyl.

The overdose data is further muddied because multiple drugs are involved in almost half of all drug overdoses.

Poor Overdose Data Concentrated in Several States

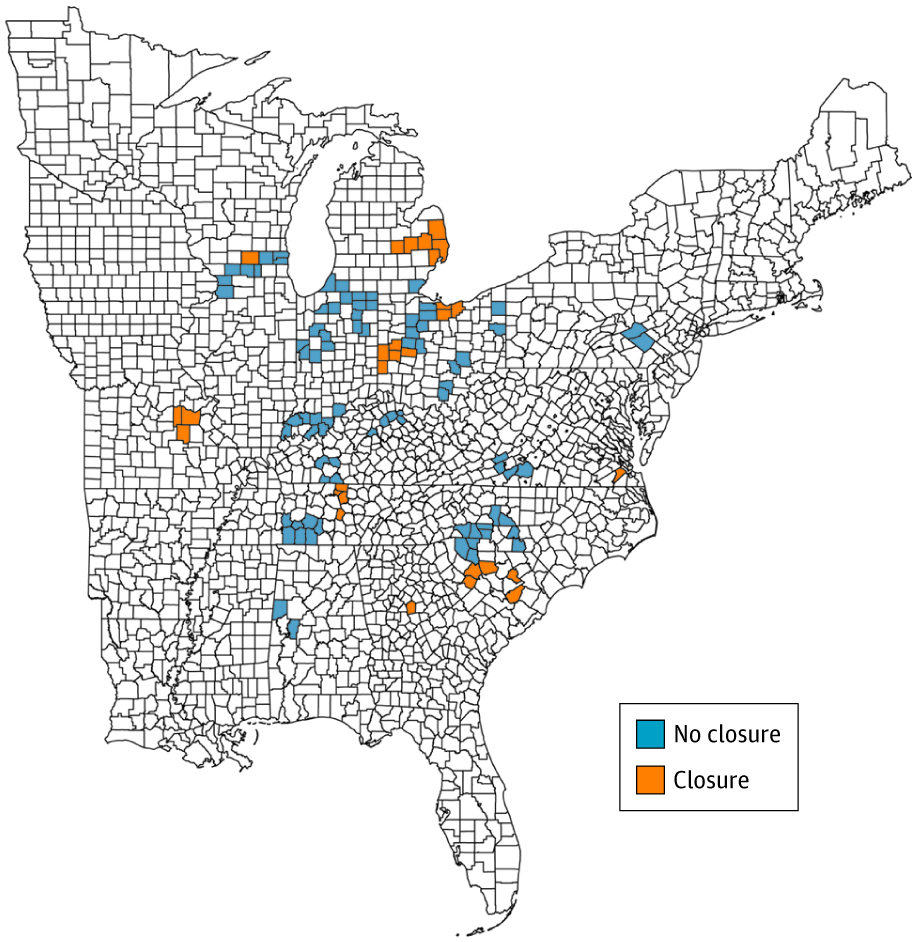

In their study, Hill and her colleagues obtained overdose death records from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics. Using statistical analysis, they correlated information on unclassified overdose deaths with potential contributing causes, such as previous opioid use and chronic pain conditions.

While the overall percentage of unclassified deaths declined over time – apparently due to efforts to improve overdose data -- the number remained high in several states. In Pennsylvania, for example, the official number of opioid-related deaths was 12,374. Researchers estimate that the actual number of deaths was 26,586.

"The underreporting of opioid-related deaths is very dependent upon location and this new data alters our perception of the intensity of the problem," said Hill. "Understanding the true extent and geography of the opioid crisis is a critical factor in the national response to the epidemic and the allocation of federal and state resources."

The CDC recently reported that drug overdose deaths dropped 4.1% in 2018 – the first decline in nearly three decades -- led by a significant drop in overdoses involving hydrocodone, oxycodone and other painkillers. But deaths linked to illicit fentanyl, methamphetamines and psychostimulants are surging, threatening to reverse the overall trend.

“One thing that we’re seeing is that the decline doesn’t appear to be continuing in 2019. It appears rather flat, maybe actually increasing a little bit,” said Robert Anderson, PhD, Chief of the Mortality Statistics Branch, National Center for Health Statistics.

Drugs Kill in Other Ways

All of these studies miss the mark, according to research published in PLOS ONE, because they don’t include deaths caused by infectious disease, drunk driving, suicide, and cardiovascular disease — all of which are affected by drug use.

"The basic records being kept are annual reports on the number of deaths from drug overdose. But that's only part of the picture,” said Samuel Preston, a professor of sociology at the University of Pennsylavnia. "Drugs can kill in other ways."

In 2016, 63,000 deaths were attributed to drug overdoses, but Preston and his colleagues estimate that the actual number of drug-associated deaths was around 142,000. Drug use shaved off nearly a year-and-a-half of life for men and three-quarters of a year for women.

"It's not just about the supply of drugs, but that there's something else behind all of it that causes people to either use drugs or alcohol or commit suicide because they've lost interest in their life," said co-author Dana Glei, a Georgetown University demographer.