Prescription Opioid Use Fell Nearly 7% in 2021

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

Prescription opioid use in the United States fell by 6.9% in 2021, the tenth consecutive year the volume of opioid pain medication has declined, according to a new report by the IQVIA Institute, a healthcare data tracking firm.

The decline in opioid consumption came even as prescription drug use overall reached record levels in 2021, fueled in part by new COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics. Spending on medicines rose 12% to $407 billion last year, according to IQVIA, with 194 billion doses of medication dispensed.

While longer opioid prescriptions were written in the early stages of the pandemic to accommodate patients who didn’t see their doctors as often, prescribing quickly returned to its decade-long downward trend.

“Prescription opioid use has fallen by 48% over the past five years and is now at levels last seen in 2000, reflecting efforts by many stakeholders to limit and manage appropriate prescription opioid use,” IQVIA said in its annual report on medicines in the U.S.

IQVIA tracks opioid prescriptions in morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs). The company estimates that per capita opioid use fell to 309 MME last year (about 0.84 MME per day), down from a peak of nearly 800 MME in 2011.

Some providers have reduced their opioid prescribing more than others. Since 2016, surgeons, anesthesiologists, dentists and general practitioners have cut their opioid prescribing by over 50 percent, while nurse practitioners and physician assistants have reduced their prescribing by 27 percent.

Prescription Opioid Use and by Prescriber Specialty

Opioid consumption by Americans has fallen so sharply in recent years that Canada, Australia and several European countries have overtaken the U.S. and become the highest consumers of opioid medication. A recent study ranks the U.S. as 8th globally in per capita opioid sales.

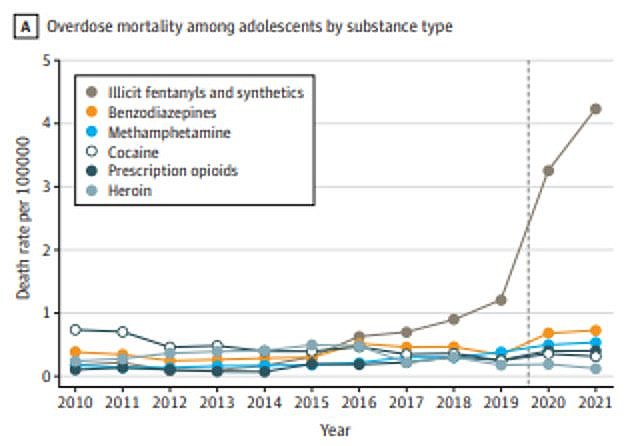

The decline in U.S. opioid prescribing has failed to stop the surge in overdoses. The CDC estimates that 106,854 people died from drug overdoses in the 12-month period ending November 2021, with drug deaths more than doubling in the last six years. Synthetic opioids – primarily illicit fentanyl – were involved in about two-thirds of fatal overdoses in the past year.

Patients Blamed for Diversion

Despite the historic decline in prescription opioid use, some politicians continue to blame opioid medication, prescribers and even patients for the nation’s overdose epidemic.

In comments recently submitted to the CDC on its revised opioid guideline, West Virginia Attorney General Patrick Morrisey and 10 other state attorneys general said the agency needs to do more to prevent the diversion of prescription opioids.

“Diversion must remain a key consideration of any prescribing guideline,” said Morrisey.

“Although drug dealers and unethical physicians are responsible for much of the opioid diversion nationwide, legitimate prescriptions remain a prime source of diversion, too. Diverted opioids most commonly reach drug abusers through friends and family members who filled a legitimate prescription.

“The amount of opioids prescribed in recent years has been excessive and far beyond the amount necessary to support legitimate medical need.”

“Indeed, the amount of opioids prescribed in recent years has been excessive and far beyond the amount necessary to support legitimate medical need. And over-prescription allows legitimate prescriptions to fall into the hands of patients’ family and friends.”

How common is it for prescription opioids to be diverted? Not common at all, according to the DEA’s National Drug Threat Assessment, an annual report that estimates less than 1% of legally prescribed opioids are diverted. “The number of opioid dosage units available on the retail market and opioid thefts and losses reached their lowest levels in nine years,” the DEA’s 2020 report found.

Despite this, Morrisey puts the onus on pain patients to prove that they’re not abusing or selling their prescriptions. He and the other attorneys general called for routine drug testing of pain patients – rejecting evidence that fraud is common is the drug testing industry and that widely used point-of-care urine tests often give false results that lead to patient abandonment.

“The given reasons that toxicology screenings might lead to ‘stigmatization,’ encourage ‘inappropriate termination from care,’ or be ‘misinterpreted’ are unsatisfactory,” Morrisey wrote. “First, what stigma would the patient face? Diagnostic results are private information. The only people who would know that the test is performed are the patient and the prescriber. The prescriber is already familiar with the patient’s prescriptions, so this process would not reveal any new information -- unless, of course, the patient had lied or not followed the prescriber’s directions.”

Remarkably, the 7-page letter from Morrisey never acknowledges that most drug deaths involve street drugs, not prescription opioids, and makes no mention of fentanyl. The most recent overdose data from West Virginia – Morrisey’s home state – indicates nearly 3 out of 4 drug deaths involve fentanyl.

Morrisey’s letter was co-signed by the attorneys general of Arkansas, Indiana, Kansas, Mississippi,

Nebraska, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Kentucky and Virginia.