What Is the Best Kind of Face Covering?

/By Dr. Lynn Webster, PNN Columnist

As we learn more about COVID-19, top health officials have updated their advice about how we can protect ourselves from the virus.

On February 29, U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams, MD, tweeted: "Seriously people- STOP BUYING MASKS! They are NOT effective in preventing general public from catching #Coronavirus."

By July 20, Adams had changed his mind and was urging the public to “wear a face covering," although he still believes that wearing a mask should not be nationally mandated.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also recommends wearing face masks when we are out in public and social distancing is difficult to maintain, or when we are around people who do not live in our household. So does the Food and Drug Administration.

There are different types of face masks, though, and some work better than others.

N95 masks provide the best possible protection, followed by surgical masks, but they should be reserved for healthcare workers. Personal protective equipment (PPE) is still in short supply globally because of hoarding, misuse and increased demand -- which puts healthcare workers and their patients at risk.

Members of the public can buy or make their own cloth masks to wear. Laboratory tests have shown that, when worn properly, cloth masks reduce the spray of viral droplets.

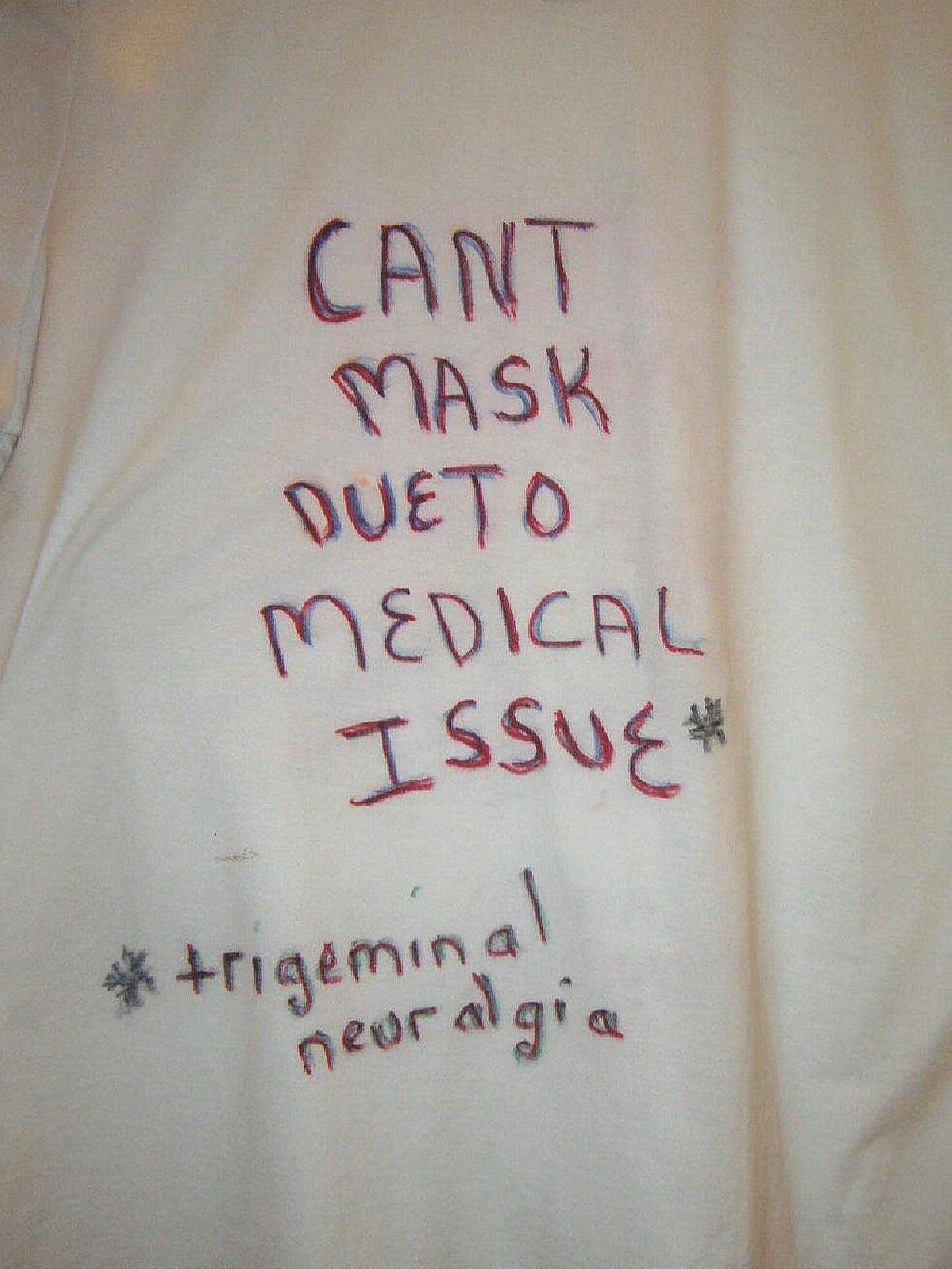

Some individuals, however, find it uncomfortable to wear a mask, or they may have a medical condition or disability that makes it difficult for them to breathe. Face masks may also fog up eyeglasses, irritate skin and inhibit communication by muffling the voice. People also frequently touch their faces to adjust or remove their masks, and that may increase the risk of infection.

Not all face masks provide equal protection. At best, cloth masks can be as effective as surgical masks. But using some variants, such as “neck gaiters” made of a polyester spandex, may even be worse than not wearing a mask at all.

Neck gaiters are less restrictive than masks, so they may be more comfortable. But their porous fabric breaks large viral particles into smaller ones, and that may allow them to linger in the air for a longer period of time. That makes them risky to the wearer and people around them.

Face Shields May Be Better Alternative

Jennifer Veltman, MD, chief of infectious diseases at Loma Linda University Health, recommends face shields made of clear plastic or plexiglass to people who are unable or unwilling to wear a mask. According to Veltman, if someone coughs 18 inches from you while you are wearing a face shield, the viral exposure is reduced by 96 percent.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar with the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, believes that face shields may eventually replace cloth masks because they are more comfortable to wear and easier to breathe with. And because they extend down from the forehead, face shields protect the eyes as well as the nose and mouth. That can be important since viruses can enter the body via the eyes. It is also easy to wipe face shields clean and reuse them.

Dr. Frank Esper, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, agrees that face shields have many benefits over cloth masks. However, they also have drawbacks. For example, he points out that viruses survive longer on plastic face shields than on cloth masks. Also, if a person wearing a face shield coughs, viral droplets can escape because of the gap between the shield and the mouth.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, says, "If you have goggles or an eye shield, you should use it. It's not universally recommended, but if you really want to be complete, you should probably use it if you can.”

White House coronavirus response coordinator Dr. Deborah Birx may have the best recommendation of all: wear a cloth mask and a face shield simultaneously. The mask, she says, protects others, while the face shields protect wearers.

Advice about how to protect ourselves will evolve as we learn more about the virus. We’ll be needing face coverings for an indefinite time period, so it is wise to become familiar with the different options for protecting yourself and your family.

Lynn R. Webster, MD, is a vice president of scientific affairs for PRA Health Sciences and consults with the pharmaceutical industry. He is author of the award-winning book, “The Painful Truth,” and co-producer of the documentary, “It Hurts Until You Die.” You can find Lynn on Twitter: @LynnRWebsterMD