Doctors Prosecuted for Opioid Prescribing Should Fight Back

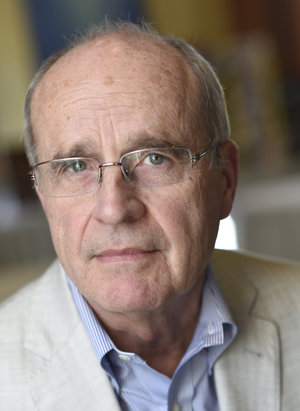

/(Editor’s note: In 2016, Dr. Mark Ibsen’s medical license was suspended by the Montana Board of Medical Examiners for his opioid prescribing practices. Two years later, the suspension was overturned by a judge who ruled that the board made numerous errors and deprived Ibsen of his legal right to due process.)

By Mark Ibsen, MD, Guest Columnist

The headlines are pretty typical: “60 Doctors Charged in Federal Opioid Sting.” The story that follows will include multiple damning allegations and innuendos, including a claim by prosecutors that they are “targeting the worst of the worst doctors.”

Sometimes there is a trial, but often the doctors plead guilty to lesser charges and give up their license rather than mount a lengthy and costly legal defense.

Why are doctors losing every case to their medical boards and DEA? Are there that many criminal doctors? If so, what happened to our profession?

I see a pattern emerging: A doctor sees patients and treats pain in the course of their practice. As other doctors give up prescribing opiates for fear of going to prison or losing their license, the ones left end up seeing more and more patients.

They soon become the leading prescribers of opioids in their state and become suspect just based on the volume of opioids they prescribe.

Given that law enforcement and medical board investigators usually don’t have training in statistics (or medicine), they are unable to see that the number of pain patients remains the same, but there are fewer practitioners willing to treat them.

“The Criminalization of Medicine: America’s War on Doctors” was published in 2007, but is even more relevant today.

“Physicians have been tried and given longer prison sentences than convicted murderers; many have lost their practices, their licenses to practice medicine, their homes, their savings and everything they own,” wrote author Ronald Libby. “Some have even committed suicide rather than face the public humiliation of being treated as criminals.”

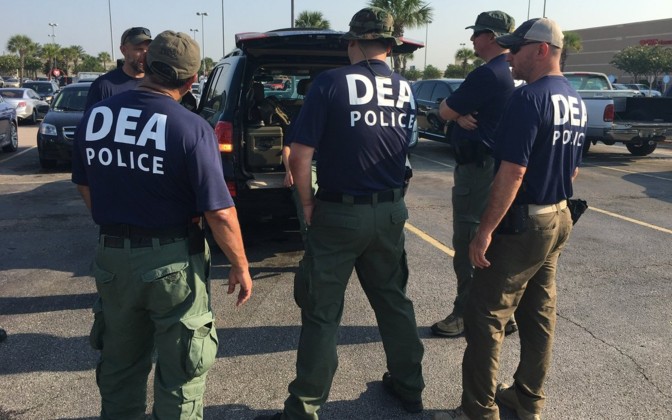

Libby wrote over a decade ago about doctors’ homes and offices being raided, DEA agents posing as pain patients to entrap them, and law enforcement task forces being created to target doctors for fraud, kickbacks and drug diversion.

Sound familiar?

I was reviewing a case about a nurse practitioner in Michigan who recently had her license suspended because she prescribed opioids “contrary to CDC guidelines” and “ranked among Michigan’s highest-volume prescribers of commonly abused and diverted controlled substances.”

This unsubstantiated crap put out by the Michigan Board of Nursing and its investigator is unethical and immoral. It should lead to a mistrial in court or dismissal at hearings.

Fight Fire With Fire

This is an Amber alert for physicians. While pejorative headlines contaminate the discourse, the prescriber’s reputation bleeds away. The Montana Board of Medical Examiners did this in my case, and since I knew that the board was relentlessly after my license for “overprescribing” opioids, I gave up any hope of fairness.

My proposal: Lawyers representing doctors must counter the negative headlines with their own, and doctors should use whatever goodwill is left to rally their staff and patients, counteracting the pressure to testify against the doctor.

I used what was left of my bully pulpit to save my own license and freedom. How? My assistant assembled my patients in large crowds at my hearings. I also made myself available to the media to counter the narrative put out by Mike Fanning, the board’s attorney, who went so far as to publicly question my sanity.

Fanning’s title was special assistant Attorney General, which told me the medical board works for DOJ in my state. I knew this for sure when DEA agents came to my office and tried to intimidate me.

“Doctor Ibsen, you are risking your license and your freedom by treating patients like these.”

Patients like what?

“Patients who might divert their medicine.”

Might? Isn’t that everyone? What would you have me do?

“We can’t tell you, we’re not doctors.”

My plea to doctors: Let’s reinvent our defense. The DEA and medical boards have a formula. It’s winning.

We need a new response: Fight back and hold on. Just like with any bully, reveal their game and fight fire with fire.

Dr. Mark Ibsen continues to practice medicine in Montana, but focuses on medical marijuana as a treatment. He no longer prescribes opioids. Six of his former patients have died after losing access to Dr. Ibsen’s care, three by suicide.

Do you have a story you want to share on PNN? Send it to: editor@painnewsnetwork.org.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.