Gabapentin Boosts High For Opioid Abusers

/By Carmen Heredia Rodriguez, Kaiser Health News

ATHENS, Ohio — On April 5, Ciera Smith sat in a car parked on the gravel driveway of the Rural Women’s Recovery Program here with a choice to make: go to jail or enter treatment for her addiction.

Smith, 22, started abusing drugs when she was 18, enticed by the “good time” she and her friends found in smoking marijuana.

She later turned to addictive painkillers, then anti-anxiety medications such as Xanax and eventually Suboxone, a narcotic often used to replace opioids when treating addiction.

Before stepping out of the car, she decided she needed one more high before treatment. She reached into her purse and then swallowed a handful of gabapentin pills.

CIERA SMITH (KAISER HEALTH NEWS)

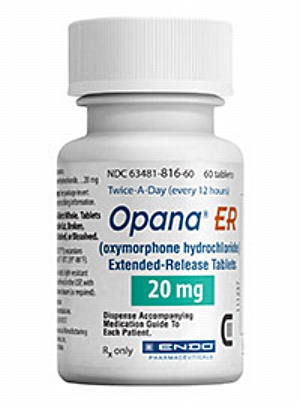

Last December, Ohio’s Board of Pharmacy began reporting sales of gabapentin prescriptions in its regular monitoring of controlled substances. The drug, which is not an opioid nor designated a controlled substance by federal authorities, is used to treat nerve pain. But the board found that it was the most prescribed medication on its list that month, surpassing oxycodone by more than 9 million doses. In February, the Ohio Substance Abuse Monitoring Network issued an alert regarding increasing misuse across the state.

And it’s not just in Ohio. Gabapentin’s ability to tackle multiple ailments has helped make it one of the most popular medications in the U.S. In May, it was the fifth-most prescribed drug in the nation, according to GoodRx.

Gabapentin is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat epilepsy and pain related to nerve damage, called neuropathy. Also known by its brand name, Neurontin, the drug acts as a sedative. It is widely considered non-addictive and touted by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as an alternative intervention to opiates for chronic pain. Generally, doctors prescribe no more than 1,800 to 2,400 milligrams of gabapentin per day, according to information on the Mayo Clinic’s website.

Gabapentin does not carry the same risk of lethal overdoses as opioids, but drug experts say the effects of using gabapentin for long periods of time or in very high quantities, particularly among sensitive populations like pregnant women, are not well-known.

As providers dole out the drug in mass quantities for conditions such as restless legs syndrome and alcoholism, it is being subverted to a drug of abuse. Gabapentin can enhance the euphoria caused by an opioid and stave off drug withdrawals. In addition, it can bypass the blocking effects of medications used for addiction treatment, enabling patients to get high while in recovery.

Athens, home to Ohio University, lies in the southeastern corner of the state, which has been ravaged by the opioid epidemic. Despite experience in combating illicit drug use, law enforcement officials and drug counselors say the addition of gabapentin adds a new obstacle.

“I don’t know if we have a clear picture of the risk,” said Joe Gay, executive director of Health Recovery Services, a network of substance abuse recovery centers headquartered in Athens.

‘Available To Be Abused’

A literature review published in 2016 in the journal Addiction found about a fifth of those who abuse opiates misuse gabapentin. A separate 2015 study of adults in Appalachian Kentucky who abused opiates found 15 percent of participants also misused gabapentin in the past six months “to get high.”

In the same year, the drug was involved in 109 overdose deaths in West Virginia, the Charleston Gazette-Mail reported.

Rachel Quivey, an Athens pharmacist, said she noticed signs of gabapentin misuse half a decade ago when patients began picking up the drug several days before their prescription ran out.

“Gabapentin is so readily available,” she said. “That, in my opinion, is where a lot of that danger is. It’s available to be abused.”

In May, Quivey’s pharmacy filled roughly 33 prescriptions of gabapentin per week, dispensing 90 to 120 pills for each client.

For customers who arrive with scripts demanding a high dosage of the drug, Quivey sometimes calls the doctor to discuss her concerns. But many of them aren’t aware of gabapentin misuse, she said.

Even as gabapentin gets restocked regularly on Quivey’s shelves, the drug’s presence is increasing on the streets of Athens. A 300-milligram pill sells for as little as 75 cents.

(kAISER HEALTH NEWS)

Yet, according to Chuck Haegele, field supervisor for the Major Crimes Unit at the Athens City Police Department, law enforcement can do little to stop its spread. That’s because gabapentin is not categorized as a controlled substance. That designation places restrictions on who can possess and dispense the drug.

“There’s really not much we can do at this point,” he said. “If it’s not controlled … it’s not illegal for somebody that’s not prescribed it to possess it.”

Haegele said he heard about the drug less than three months ago when an officer accidentally received a text message from someone offering to sell it. The police force, he said, is still trying to assess the threat of gabapentin.

Little Testing

Nearly anyone arrested and found to struggle with addiction in Athens is given the option to go through a drug court program to get treatment. But officials said that some exploit the absence of routine exams for gabapentin to get high while testing clean.

Brice Johnson, a probation officer at Athens County Municipal Court, said participants in the municipal court’s Substance Abuse Mentally Ill Program undergo gabapentin testing only when abuse is suspected. Screenings are not regularly done on every client because abuse has not been a concern and the testing adds expense, he said.

The rehab program run through the county prosecutor’s office, called Fresh Start, does test for gabapentin. Its latest round of screenings detected the drug in five of its roughly 238 active participants, prosecutor Keller Blackburn said.

Linda Holley, a clinical supervisor at an Athens outpatient program run by the Health Recovery Services, said she suspects at least half of her clients on Suboxone treatment abuse gabapentin. But the center can’t afford to regularly test every participant.

Holley said she sees clients who are prescribed gabapentin but, due to health privacy laws, she can’t share their status as a person in recovery to an outside provider without written consent. The restrictions give clients in recovery an opportunity to get high using drugs they legally obtained and still pass a drug test.

“With the gabapentin, I wish there were more we could do, but our hands are tied,” she said. “We can’t do anything but educate the client and discourage” them from using such medications.

A stone painted with the phrase “Perfect Imperfection” is among the inspirational messages along the sidewalk leading to the main entrance of the Rural Women’s Recovery Program. (Carmen Heredia Rodriguez/KHN)

Smith visited two separate doctors to secure a prescription. As she rotated through drug court, Narcotics Anonymous meetings, jail for relapsing on cocaine and house arrest enforced with an ankle bracelet, she said her gabapentin abuse wasn’t detected until she arrived at the residential recovery center.

Today, Smith sticks to the recovery process. Expecting a baby in early July, her successful completion of the program not only means sobriety but the opportunity to restore custody of her eldest daughter and raise her children.

She intends to relocate her family away from friends and routines that helped lead her to addiction and said she will help guide her daughter away from making similar mistakes.

“All I can do is be there and give her the knowledge that I can about addiction,” Smith said, “and hope that she chooses to go on the right path.”

Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit health newsroom whose stories appear in news outlets nationwide, is an editorially independent part of the Kaiser Family Foundation.