New Rule Expands Access to Buprenorphine

/By Pat Anson, Editor

This week marks the start of a major expansion in access to buprenorphine – a medication that is both widely praised for treating opioid addiction and also blamed for fanning the flames of abuse and diversion.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) updated a federal rule, nearly tripling the number patients that can be treated with buprenorphine by an eligible physician.

Raising the limit from 100 to 275 patients is intended to give addicts greater access to buprenorphine, especially in rural areas where few doctors are certified to prescribe the drug. According to HHS, over two million people who are dependent on heroin and other opioids could benefit from buprenorphine treatment.

“For too long, addiction specialists like me have had to turn patients in need away from treatment that might save their lives, not because we don’t have the expertise or capacity to treat them, but because of an arbitrary federal limit,” said Dr. Jeffrey Goldsmith, President of the American Society of Addiction Medicine .

But critics of the rule change say there will be a price to pay.

“Buprenorphine is one of the most abused pharmaceuticals in the world,” warns Percy Menzies, president of Assisted Recovery Centers of America, which operates four addiction treatment clinics in the St. Louis area.

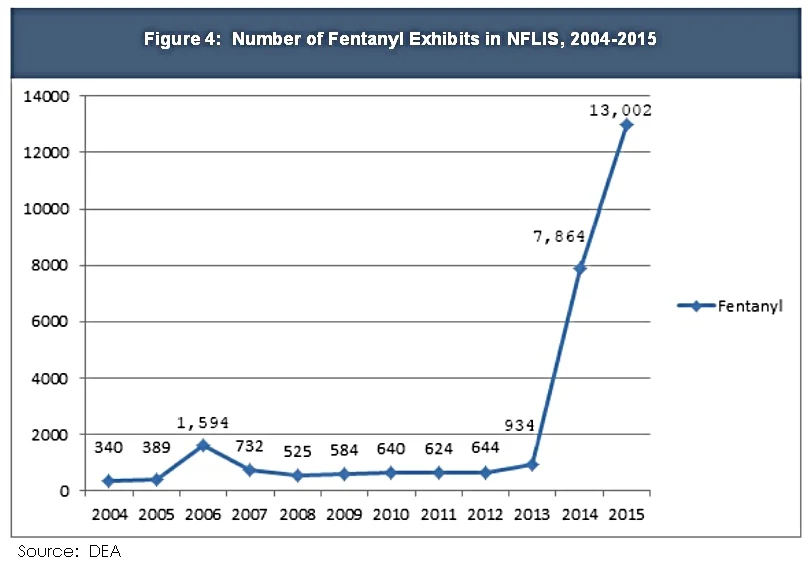

“Sales of buprenorphine formulations have exceeded $2 billion a year, but we have not had any lessening of heroin addiction. Increased access to buprenorphine and increased availability of potent heroin and heroin laced drugs like fentanyl will only exacerbate the problem.”

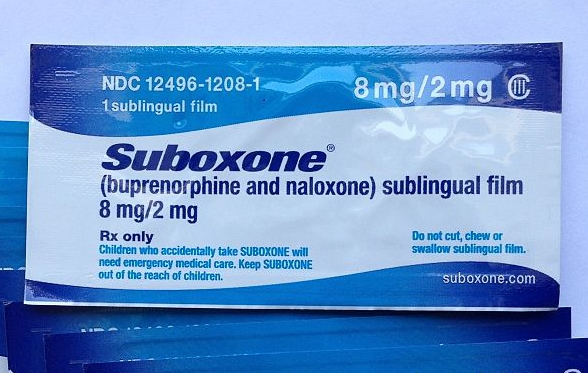

The problem with buprenorphine is that it’s an opioid that can be used to treat pain or addiction. When combined with naloxone, buprenorphine reduces cravings for opioids and lowers the risk of abuse. For many years the drug was sold exclusively under the brand name Suboxone, but it is now produced by several different drug makers and is sold in tablets, sublingual films and even an implant.

Addicts long ago discovered that buprenorphine can also be used to get high or to ease their withdrawal pains from heroin and other opioids. Buprenorphine is such a popular street drug that the National Forensic Laboratory Information System ranked buprenorphine as the third most diverted opioid medication in the U.S. in 2014.

“Too many physicians erroneously believe that naloxone in the formulation makes the drug safe,” Menzies said in an email to Pain News Network. “Increasing the limit is definitely going to increase diversion. The majority of the physicians prescribing buprenorphine do not provide any comprehensive relapse prevention counseling, random drug testing, etc. In the absence of standards for treating addictive disorders, anything goes and will be no different than treating chronic pain.

“We saw the problem with prescription opioids when opioids were promoted as safe and non-abusable in the treatment of chronic pain. Very quickly the numbers grew into the tens of millions and the addiction exploded. The unintended victims were the patients in genuine chronic pain.”

Menzies uses buprenorphine as an initial treatment for opioid addiction in his clinics, but prefers another medication -- naltrexone -- for long-term maintenance therapy. He says doctors who rely on buprenorphine exclusively will, in effect, be sentencing their patients to lifetime use of the drug.

"Financial Opportunity" for Doctors

HHS acknowledges there could be “unintended negative consequences” to increased prescribing of buprenorphine. One is diversion. Another is an increase in patient volume, physician profits and buprenorphine “pill mills” – which are already popping up in states like Florida. Patients typically pay cash for buprenorphine at those clinics and receive little or no addiction counseling or services.

“This proposed rule directly expands opportunities for physicians who currently treat or who may treat patients with buprenorphine,” HHS said in an extensive analysis of the rule change. “We believe that this may translate to a financial opportunity for these physicians.”

HHS estimates the cost of treating new buprenorphine patients at up to $313 million in the first year alone. Many of the patients are low-income and the bills for treating them – about $4,300 annually for each patient – will often be covered by Medicaid. The additional cost of treating these patients, according to HHS, will be offset by the health benefits achieved by getting addicts into treatment, which the agency generously estimates at $1.7 billion.

The Obama administration asked Congress for nearly $1 billion in additional funding to help pay for addiction treatment, but didn’t get it in when Congress passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA Act). The President reluctantly signed the bill into law anyway.

A little noticed provision of the CARA Act is that it expands access to buprenorphine even further. Currently only a trained and certified physician can prescribe buprenorphine, but CARA requires HHS to update its rules within 18 months to allow nurse practitioners and physician assistants to prescribe buprenorphine, provided they undergo training first.

How can buprenorphine diversion be prevented when access to it is rapidly increasing?

One solution proposed by Menzies is to change the classification of buprenorphine from a Schedule III controlled substance to a Schedule II drug – the same classification change that hydrocodone went through in 2014. Such a move would limit buprenorphine prescriptions to an initial 90-day supply and require patients to see a doctor for a new prescription each time they need a refill.

“We are caught between a rock and a hard place. We need to increase access to buprenorphine and it will lead to increased diversion and abuse, and therefore I am recommending changing the schedule,” Menzies said in his email to PNN.

“This is the psychotic state of affairs! No chronic condition/disease/disorder has ever been successfully treated with an addicting drug and we think we can do it for opioid addiction!”