Letters to Doctors Reduced Their Opioid Prescribing for a Year

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

Many doctors in the U.S. have scaled back or stopped prescribing opioid pain medication because they fear scrutiny or even imprisonment by the DEA and other law enforcement agencies.

A team of USC researchers believes there’s a better way to address risky opioid prescribing: have coroners and medical examiners notify all doctors by letter when a patient dies from an overdose.

“This is not meant to be a law enforcement exercise but a simple nudge. The point is not to scare, blame or shame doctors, but to make them aware of real risks in their patient cohorts, risks they may not be aware of otherwise,” says Jason Doctor, PhD, Professor and Chair of Health Policy and Management at USC’s Sol Price School of Public Policy.

Doctor and his colleagues found that when 809 prescribers received a letter from San Diego county’s medical examiner notifying them about the overdose death of a patient, they reduced the doses of opioid prescriptions they wrote for up to a year afterward. Their findings, published in JAMA Network Open, builds upon a previous study that found the same clinicians reduced their prescribing for three months after receiving such a letter.

"Clinicians don't necessarily know a patient they prescribed opioids to has suffered a fatal overdose," said Doctor. “We knew closing this information loop immediately reduced opioid prescriptions. Our latest study shows that change in prescribing behavior seems to stick."

Nationwide, opioid prescribing has fallen dramatically over the past decade. But USC researchers found the reduction was faster and more extensive among clinicians who received the letter. After one year, their prescriptions were 7.1% lower in morphine milligram equivalent units (MME) than clinicians who hadn't received the letter. The number of new patients they prescribed opioids to also fell by two percent.

"The new study shows this change is not just a temporary blip and then clinicians went back to their previous prescribing," said Doctor. "This low-cost intervention has a long-lasting impact."

Other Drugs Often Involved

There are three major caveats to the USC study. The first is that other substances besides prescription opioids – such as illicit drugs -- were involved in many of the overdose deaths. That’s because the criteria for the study were broad and subjective, including any patient who died when "prescription drug overdose was the primary cause or contributed to the cause of death."

Second, clinicians were included in the study if they had written any opioid prescription within 12 months of the patient’s death. That would explain why 809 prescribers received letters about the overdoses of 166 patients. Doctors received a letter even if a patient was no longer under their care and without conclusive evidence that the prescription they wrote was involved in the death.

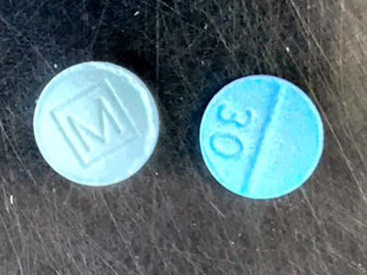

Third, the study does not address the growing number of deaths caused by illicit fentanyl, which is now responsible for the vast majority of U.S. overdoses. Letters to doctors are unlikely to have any major effect on overdoses involving street drugs. A 2022 study confirmed there is very little correlation between overdoses, prescription opioids and MME dosage levels.

There have been several previous efforts to rein in opioid prescribing by sending warning letters to doctors. Federal prosecutors in Wisconsin and other states have done it, telling high-dose prescribers they could face prosecution, even when they have not been charged with a crime or linked to an overdose.

The Medical Board of California’s “Death Certificate Project” sent threatening letters to doctors about overdoses that occurred months or years after an opioid prescription was written -- an effort that some likened to a “witch hunt.” Some doctors were targeted even when multiple drugs were involved or the cause of death was suicide.

USC’s Doctor says a gentler “nudge” is needed, not threats. And he wishes the letters sent to San Diego doctors were mandatory statewide.

“That was a terrible approach to delivering letters that the medical board carried out,” Doctor wrote in an email. “We had none of the outcry or problems the (board) did because we were supportive and met clinicians on a professional level.”