What Kind of Pain Care Would JFK Get Today?

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, an event that shocked the world. Kennedy was only 46 when he died in 1963.

At the time, Kennedy was widely seen as a healthy, handsome and vigorous man. The truth, which emerged years later, is that JFK was chronically ill almost from birth. Scarlet fever nearly killed him as an infant, and as a child he was thin, sickly, and suffered from chronic infections and digestive problems.

Not until decades after his death did we learn that Kennedy was born with an autoimmune condition called polyglandular syndrome, and that a series of failed back surgeries may have led to adhesive arachnoiditis, a chronic and painful inflammation in his spinal canal. Historians and physicians also confirmed rumors that JFK suffered from Addison’s Disease, a well-guarded family secret.

Kennedy was given the last rites at least twice before becoming president and reportedly told his father that he would “rather be dead” than spend the rest of his life on crutches, paralyzed by pain.

In short, it’s a bit of miracle that JFK even lived to see his 46th birthday. The American public never had a full understanding of his health problems until long after he was dead.

How did Kennedy pull it off? The answers can be found in Dr. Forest Tennant’s latest book, “The Strange Medical Saga of John F. Kennedy.”

“The reason I decided to write it was mainly that I had become aware that he was an intractable pain patient,” says Tennant, a retired physician and one the world’s foremost experts on arachnoiditis and intractable pain. “Fundamentally, my book is really taking a lot of other people's work and putting it together in a historical chronological fashion. I just felt it needs to be done to really understand what happened to him.”

Although Kennedy’s chronic health problems were largely hidden from the public, many of his medical records still exist – a reflection of his family’s wealth and access to the best medical care available. Good doctors keep good medical records, especially when their patients are rich and famous.

“Until I got into doing this, it was not appreciated by me. Unless a person is very famous and has a lot of medical records, physicians never get to see a case from start to finish. Meaning from birth to death. I've never really realized how rare that is,” says Tennant.

A Controversial Drug Cocktail

In the mid 1950’s, Kennedy found a team of innovative medical experts who helped relieve his pain, elect him as president, and achieve his best health ever while living in the White House.

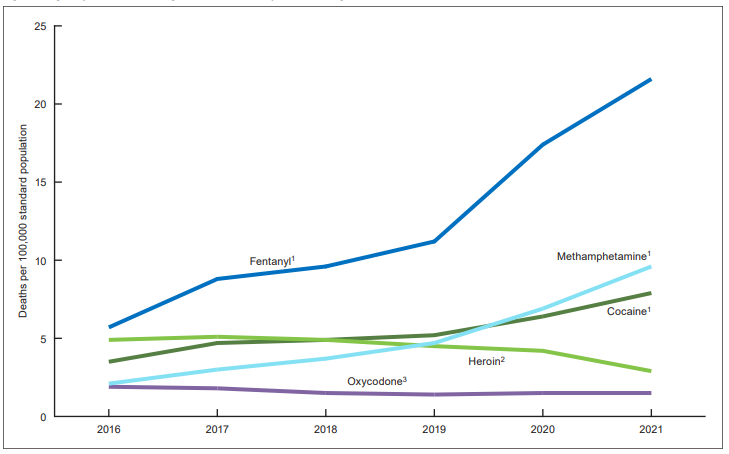

Dr. Max Jacobson put Kennedy on a controversial “performance enhancing” cocktail. The ingredients were secret, but Tennant says the cocktail probably included methamphetamine, hormones, vitamins and steroids.

Exhausted from months of campaigning, Kennedy was injected with the cocktail just hours before his first debate with Richard Nixon, a nationally televised debate that likely won the election for Kennedy because he appeared more energetic than Nixon.

Kennedy continued taking the cocktail as president, over the objections of White House physicians.

High Dose Opioids

Dr. Janet Travell also played a key role in revitalizing Kennedy’s health, putting him on a comprehensive pain management program that included physical therapy, hormone replacement, anti-inflammatory drugs, and the opioids methadone, codeine and meperidine (Demerol).

One of the first things she noticed was the callouses under Kennedy’s armpits from using crutches so often.

“On the day she met him, she put him in a hospital and started methadone that day, as a long-acting opioid, and then she also had him on Demerol and some other miscellaneous opioids. But his two main opioids were methadone and then Demerol for breakthrough pain,” said Tennant.

The precise dosage given to JFK is unknown, but Tennant estimates it was initially 300 to 500 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) a day, a level that would be considered risky under the CDC’s 2016 opioid prescribing guideline. The guideline recommended that dosages not exceed 90 MME.

“It would have exceeded the CDC guidelines by far,” says Tennant. “The methadone dose would have exceeded the CDC guidelines itself. But she knew to put him on methadone and if it hadn't been for methadone, he’d never have been president. He had to have something to stabilize himself right at that time. And he had to have a second opioid for breakthrough pain.”

Dosages that high today would likely attract the attention of the Drug Enforcement Administration, which investigates and prosecutes doctors for writing high-dose prescriptions. Tennant himself came under scrutiny from the DEA for giving intractable pain patients high doses, and his office and home were raided by DEA agents in 2017. Tennant was never charged with a crime, but he retired from clinical practice a few months later.

Raids like that have had a chilling effect on doctors nationwide. Many now refuse to see pain patients on opioids, regardless of the dose.

“JFK would not have been welcome today in pain clinics,” says Tennant. “My patients were very similar to JFK, almost same disease, same kind of doses, and the same kind of therapies. And of course, today that is taboo. But that was the standard in the 1950’s.

“It's only been in the last few years that the government has decided that the standard treatment that has been there for half a century is now almost a crime.”

Dr. Travell never came under that kind of scrutiny, but Dr. Jacobsen did. Dubbed “Dr. Feelgood” by critics for his unconventional treatments, Jacobson’s medical license was suspended in New York state a few years after Kennedy’s death. The 1972 Controlled Substances Act ensured that his cocktail would never be prescribed again.

Tennant says there is no evidence the cocktail harmed or impaired JFK, who was never hospitalized or bed-bound during the 8 years he was under Jacobson’s care.

Without Jacobson and Travell, Tennant believes it unlikely Kennedy would have run for president or been elected.

“That's one of the reasons why I wrote the book. I think people need to know that JFK’s treatment was opioids. And his treatment was the standard of the day, up until the recent fiat by the federal government and state medical boards. The country got along for half a century with those standards quite well,” Tennant said.

In addition to his book about JFK, Tennant has written books about Howard Hughes and Elvis Presley, who also lived with -- and overcame -- chronic health problems.

The Tennant Foundation gives financial support to Pain News Network and sponsors PNN’s Patient Resources section.