Will Thinking About Chronic Pain Differently Help Reduce It?

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

Want to make your chronic back pain go away?

Then stop thinking about the physical cause of your pain with words like accident, bad posture or disc bulge.

Start attributing the cause of your pain to your own emotions. Use words like anxiety, stress and fear.

That’s the conclusion of a new analysis of an old study that found pain reprocessing therapy (PRT) beneficial in a small group of patients with chronic back pain. PRT is based on the theory that patients can reduce or even stop their pain simply by changing the way they think about it, without the use of drugs, injections or physical therapy.

“Millions of people are experiencing chronic pain and many haven’t found ways to help with the pain, making it clear that something is missing in the way we’re diagnosing and treating people,” says lead author Yoni Ashar, PhD, assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

“Our study shows that discussing pain attributions with patients and helping them understand that pain is often ‘in the brain’ can help reduce it.”

Ashar and his colleagues were early proponents of PRT. In a 2021 clinical study, they recruited 151 people with moderate back pain, with an intensity of at least four on a pain scale of zero to 10. Participants assigned to PRT were encouraged to reappraise the severity of their pain and to think about it differently by engaging in movements they were afraid to do. About two-thirds found that helpful in reducing or even eliminating their pain.

In their new study, published in JAMA Network Open, researchers doubled down on their previous study by performing a “secondary analysis” of those same 151 people. Did they attribute their pain to a physical or emotional cause? What words did they use to describe it?

Before PRT treatment, only 10% of participants’ thought their back pain was mind or brain-related. After PRT, about half of them did. And the more they thought about their pain as a mind or brain process, the greater the reduction in pain they reported.

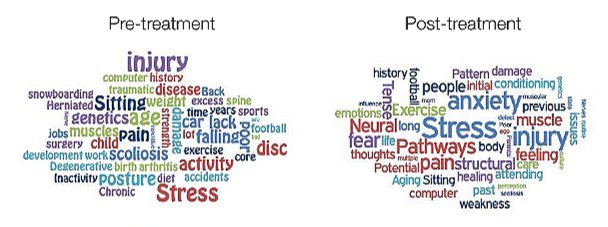

The graphic below demonstrates how participants thought about their pain differently before and after PRT. In a word cloud text analysis of their responses, PRT recipients were more likely to use words like stress and anxiety, and less likely to use words like muscles and injury.

Words Associated with Chronic Pain Before and After PRT

JAMA NETWORK OPEN

“These results show that shifting perspectives about the brain’s role in chronic pain can allow patients to experience better results and outcomes,” Ashar said.

“This study is critically important because patients’ pain attributions are often inaccurate. We found that very few people believed their brains had anything to do with their pain. This can be unhelpful and hurtful when it comes to planning for recovery since pain attributions guide major treatment decisions, such as whether to get surgery or psychological treatment.”

There are a number of caveats to this study. First is the small size. Second, participants had only low to moderate back pain, not the severe intractable pain caused by a spinal injury or disease. Thinking about your pain differently isn’t going to do much good for someone with arachnoiditis or Ehlers Danlos syndrome – and it is worrisome that studies like these are often used to deny patients with severe pain access to effective treatment such as opioid medication.

Third, pain reattribution was only modestly effective (about 9% on average) in relieving pain. Some participants who bought into the idea of thinking differently about their pain had no pain relief, leading the authors to admit that “reattribution alone is not sufficient for pain relief.”

Despite these weaknesses, researchers hope their study will encourage providers to talk to their patients more about the possible causes of their chronic pain.

“Often, discussions with patients focus on biomedical causes of pain. The role of the brain is rarely discussed,” said Ashar. “With this research, we want to provide patients as much relief as possible by exploring different treatments, including ones that address the brain drivers of chronic pain.”

You can learn more about PRT therapy by reading “The Way Out,” a book by psychotherapist Alan Gordon, who uses mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy to reduce the fear that many patients have about their pain and its triggers.