Why Pain Patients Should Worry About Chris Christie

/(Editor’s Note: Last month President Donald Trump named New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie as chair of a new commission that will study and draft a national strategy to combat opioid addiction..

Gov. Christie has been a prominent supporter of addiction treatment and anti-abuse efforts.

He also recently signed legislation to limit initial opioid prescriptions in New Jersey to five days, a law that takes effect next month.)

white house photo

By Alessio Ventura, Guest Columnist

Unfortunately, Chris Christie's crackdown on opioids will have extremely negative consequences for people with acute and chronic pain in New Jersey. It is equivalent to gun control, where because of crime and mass shootings, innocent gun owners are punished.

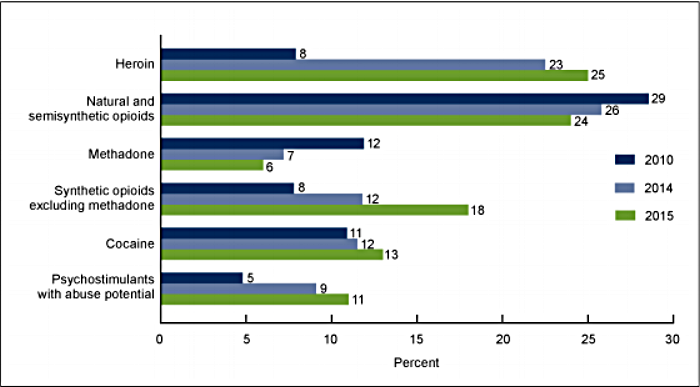

The fact is that only a small percentage of opioid deaths are from legitimate prescriptions. Most overdose deaths are from illegal drugs or the non-medical use of opioids.

The government crackdown on opioids has created a literal hell on earth for people with severe pain, who often can no longer find the medication they need. This has become a major issue, even though there are other drugs that are just as dangerous when misused:

- Every year 88,000 people die from alcohol poisoning. There is no government war on alcohol.

- Every year over 40,000 people die from antidepressants. There is no government war on antidepressants.

- Every year 15,000 people die from non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and 100,000 are hospitalized. There is no government war on NSAIDs.

Deaths from alcohol, antidepressants and NSAIDs far exceed deaths from opioids, yet it is opioid medication that gets all of the attention.

So when we see Chris Christie leading a new opioid commission, we chronic pain patients know full well that this just means more restrictions for us. Addicts and criminals will continue to support their habit through the illegal market, and pain patients will continue to live a life of hell that will only get worse. Most of us don’t go to the black market to buy pain medication. We drive around in excruciating pain looking for a pharmacy that can fill our prescriptions.

We also cringe in fear every time we see the "opioid epidemic" headlines and the new initiatives to combat overdoses, because we know that we will pay the price, not the addict or criminal. It’s like when a nut case opens fire and kills people. Gun owners know that new restrictions will impact them, not the criminals.

New Jersey’s 5-Day Limit on Opioids

Gov. Christie recently pushed for and convinced the New Jersey legislature to pass very restrictive pain medicine laws. Physicians in New Jersey were very much opposed to Christie's model, but it was forced upon them anyway. Since I am originally from New Jersey and most of my family still lives there, I know firsthand the devastating consequences these restrictions could have on family members.

I have had 18 invasive surgeries since 2008 and recently suffered from a sepsis infection after shoulder replacement surgery. The infection required 3 additional surgeries, two of which were emergency surgeries as the infection spread. I was fed broad spectrum antibiotics intravenously 3 times per day.

I also suffer from chronic pain from arthritis. I have tried every other pain treatment modality, and opioid-based pain medicine is the only one that works for me.

There is no way I would have been able to get up after a 5 days to visit my doctor just to refill pain medicine. But if New Jersey’s law were instituted in Florida, where I now live, it would require me to do just that. After the surgery, I was dealing with horrible pain in my shoulder, along with severe fatigue and other complications. Thank God that Florida law still allows for prescriptions of pain medicine beyond 5 days.

Chris Christie is now leading a study for President Trump, and my fear is that a new executive order will be forthcoming which will force the New Jersey model of restricting pain medicine across every state, including Florida.

Let me relay to you a recent experience of my 85 year old mother, who had invasive back surgery in New Jersey. They sent her home after 2 days in the hospital with a prescription for a 5 day supply of Percocet, and strict orders to "NOT MOVE FROM BED.”

There is already a shortage of pain medicine in New Jersey pharmacies. My sister took the script, started at a pharmacy in Bridgewater, and worked her way on Route 22 toward Newark. She visited 30 pharmacies along the way and was unable to find the medicine. She called me in tears because my mother was in terrible pain.

My sister even took my mother to the ER, but they would not give her any medicine for pain.

Thankfully, after asking several friends for help, my sister received a call from her best friend, who found a pharmacy that had Percocet. My mother received significant relief from the pain medicine, but 5 days was not nearly enough. My sister lives with my mother and was able to take her on the 4th day to see the doctor about a refill, but she never should have gotten out of bed. She was under strict orders to stay in bed, use a bed pan and not to get up until two weeks after the surgery.

Yet now on the 4th day she had no choice because of her pain. The patient has to be present to receive a new script for opioids in New Jersey, so my sister could not visit the doctor's office to pick up a script for her without my mother's presence.

This is an unbelievable intrusion into the doctor-patient relationship. Why is it that politicians are so hell bent on government intrusion when it comes to legitimate use of medicines? This is insanity.

It is time for a full court press in Washington DC. If you have acute, chronic or intractable pain, then you better wake up and do something to preserve your rights. Chronic pain is a disease, and for people who have tried all modalities and found that opioids are the only solution, you are about to lose access to the medicine that gives you some semblance of a normal life. I anticipate that an executive order mirroring the misguided New Jersey restrictions will be issued by President Trump, in essence trampling on your ability to obtain pain relief.

I am imploring you to make our voices heard. We should not be further punished because of people with addiction illness. Of course they need to be helped, but restricting access for law abiding, non-addicted patients is an outrage. It is already difficult enough to get pain medicine in Florida, often requiring visits to 20 or more pharmacies before one finds a pharmacist willing to fill a script.

I have often thought about suicide because of my pain. Many others have as well. If additional restrictions are forthcoming from Washington, then many of us will face life or death decisions. Please do not allow Chris Christie to tip the balance.

Alessio Ventura lives with chronic arthritis and post-surgical pain. He shared his experiences as a pain patient in a previous guest column. Alessio was born in Italy, came to the U.S. at age 17, and finished high school in New Jersey. He worked for Bell Laboratories for 35 years as a network and software engineer.

Pain News Network invites other readers to share their stories with us. Send them to: editor@PainNewsNetwork.org.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.