My Life as a Teen with Chronic Pain

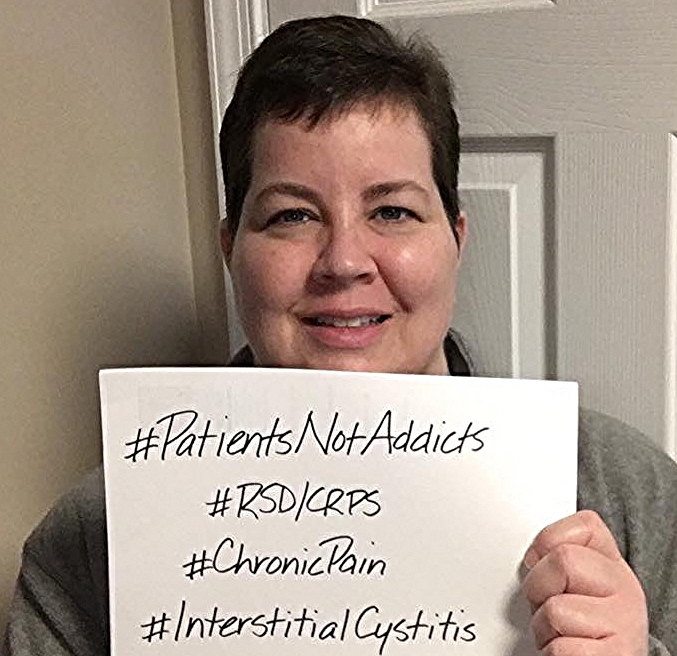

/By Stacy Depew Ellis, Guest Columnist

School, sports, music, catching up on the latest gossip. That is what I wish I could say my teenage years were filled with.

Don’t get me wrong, I had a great life. However, I was more concerned with being at school, when my last dose of medicine was, and how I was going to get up the stairs.

When I was in eighth grade, I had a traumatic accident in my dance class. After being misdiagnosed and put in a cast for almost three months, I was diagnosed with a chronic pain syndrome called Reflex Sympathetic Disorder (RSD) or CRPS.

I was sent to yet another doctor to see about treatment. It was decided that I would continue taking pain medication and start receiving lumbar injections. Little did I know that sleepless nights and several emergency room trips would also be included. I would be given more than the recommended amount of painkillers and would still be screaming in pain. Every trip back there offered more questions about a teenager being addicted to prescription drugs. Every doctor in town had seen me.

I started high school as a homebound student. I was going to school for my elective classes and seeing a teacher at my house for core classes. A lot of kids my age got hurt, most of them had a cast at some point. But my illness wasn’t visible; you couldn’t see anything wrong with me. I began losing friends and rumors spread like wildfire throughout my community and school. The worse my pain was, the worse the rumors were. It was tough, but I got through school.

STACY DEPEW ELLIS

After my 33rd spinal injection, I put a stop to the poking and prodding. The doctor hit a nerve and I was paralyzed from my shoulder to my finger tips for two days. Forty-eight hours of not moving an arm. Even more doctors came to see me and I started what would become the first of many steroid treatments.

Time went by and nothing got better. I had headaches, achiness, and started having trouble putting my thoughts into sentences. I saw a neurologist who once again started a smorgasbord of tests. Using my body as a human cushion was normal. What seemed like years of MRIs, spinal taps, and some things I have never heard of, led to the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis.

MS? Really? I was 21 years old. My first round of treatment was a huge dose of steroids. I took 150 Prednisone pills followed by three days of IV steroids. My flare ups were bad, leaving me in the hospital for weeks at a time. I was a guinea pig for these pharmaceutical companies, injecting myself with a different medicine every month to see which worked best.

It was relieving to finally have a diagnosis and know what was wrong, but having MS is almost worse than not knowing. Heaven forbid I get sick and need to see a doctor. No one wants to treat someone with something like MS. Doctors immediately go to “it’s just the MS” and real problems get overlooked and never fixed. Honestly, the dentist even has trouble being your doctor.

I have been on medicine almost my whole life. I have been seen for depression and spent my paychecks on medical bills. There may never be a cure for multiple sclerosis and I may always be popping pills and injecting things into my stomach, but I am happy to say that I do my hardest to not let my disability hinder me. I try to not let it even be a part of me and I live my life to the fullest.

I will be on anti-anxiety medicine forever but I also believe that I can do anything that I desire. That is something that no doctor can ever take from me.

Stacy Depew Ellis lives in Alabama with her husband. Stacy proudly supports the Alabama-Mississippi National Multiple Sclerosis Society and the Ronald McDonald House Charity, which provided housing for Stacy and her mother when she was in a treatment program in Philadelphia.

Pain News Network invites other readers to share their stories with us. Send them to: editor@PainNewsNetwork.org.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represent the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.