CDC: We Need Safer, More Effective Pain Relief

/(Editor’s Note: Debra Houry is director of the CDC's National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, which is developing new opioid prescribing guidelines that the agency plans to adopt in January 2016. We have many questions about the guidelines and the manner in which they are being drafted, and asked for an interview with Dr. Houry. She declined, as did CDC Director Tom Frieden. Dr. Houry did offer to write a column about the guidelines for our readers and we agreed to publish it.)

By Debra Houry, MD, Guest Columnist

At CDC I see the numbers. The numbers of people dying from an overdose of opioid pain medications. And, many of these unintentional deaths were in patients taking medications for chronic pain.

But to me, it’s not about numbers. It’s about the people. I’m concerned about stories we’ve heard at CDC from people like Vanessa and Carl, who were both prescribed opioid pain medications after car crashes. Vanessa was 17 years old when she was prescribed opioids the first time, and within several years, she was abusing IV drugs and was afraid she was going to die with a needle sticking out of her arm. Carl became addicted quickly and suffered from withdrawal when he tried to stop. He became a drug dealer to get access to the drugs that would prevent the unbearable withdrawal symptoms caused by his opioid addiction. Thankfully both Vanessa and Carl got into treatment and have been in recovery for several years now.

As an ER doctor I’ve cared for people like Carl and Vanessa suffering from traumatic injuries or in chronic pain. I’ve also had to be the one to tell families that they lost a loved one to an overdose of prescription opioids. I see the risks. It worries me when patients return because their opioid medications are no longer effective at relieving their pain, and they need larger and larger doses. Although opioids are powerful drugs that are important to manage pain, they have serious risks, with multiple side effects and potential complications, some of which are deadly.

But I want patients for whom the benefits outweigh the risks, to be able to get these important pain medications. And, I need to be able to treat pain more safely and effectively so that people can have relief without the risk of abuse, overdose or death.

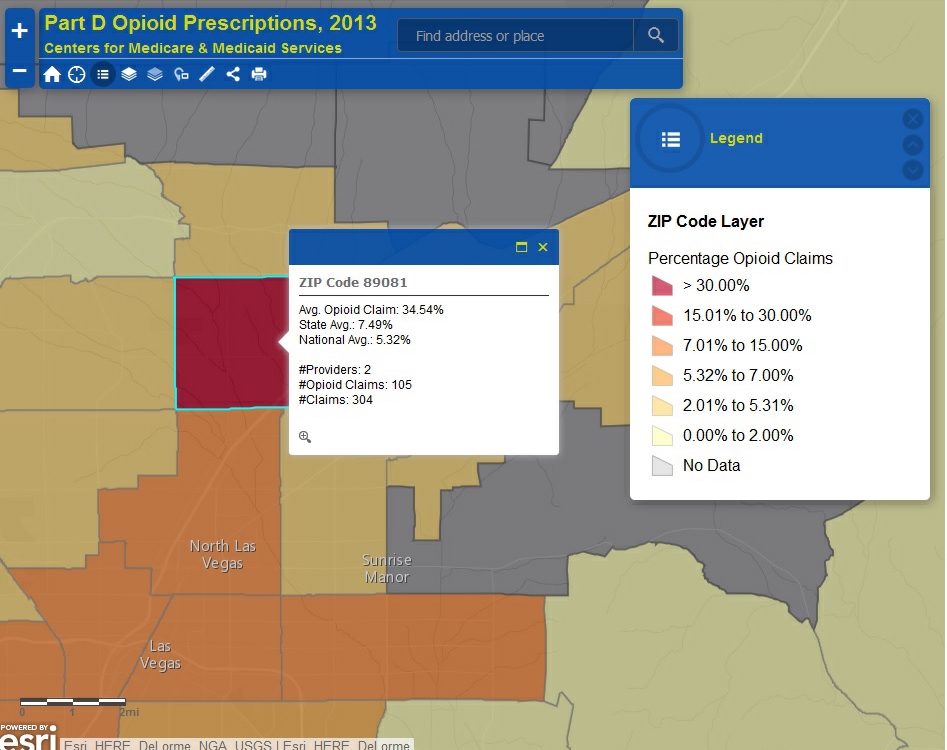

Since 1999, we’ve seen a dramatic increase in the amount of opioid pain medications prescribed in the U.S. and at the same time overdose deaths from these medications have quadrupled. The evidence is becoming clearer that overprescribing these medications leads to more abuse and more overdose deaths. Guidelines that help doctors and other health care providers work with their patients to determine if and when opioid medications should be given as part of their overall pain management strategy need to be updated.

Most of the existing guidelines have focused safety precautions on high-risk patients, and have recommended use of screening tools to identity patients who are at low risk for opioid abuse. However, opioids pose a risk to all patients, and currently available tools cannot rule out risk for abuse or other serious harm outside of end-of-life settings.

We must find a better way to treat pain so that diseases, injuries or pain treatments themselves don’t stop people from leading full and active lives. That is why CDC is working with doctors, other health care providers, partners, and patients on urgently needed guidelines based on the most current facts about safer and effective pain treatment. In a national health crisis like this one, our priorities are clear. First, take swift action to protect and save lives. Second, use world class science and proven processes to determine further improvements. And third, use the facts to prevent this situation from happening in the future.

The upcoming CDC guidelines will provide recommendations on providing safer care for all patients, not just high-risk patients. The guidelines will also incorporate recent evidence about risks related to medication dose and encourage use of recent technological advances, such as state prescription drug monitoring programs.

The guidelines are intended to help providers choose the most effective treatment options for their patients and improve their patients’ quality of life. Currently, 44 Americans die each day as a result of prescription opioid overdose. By providing the tools to help physicians make informed prescribing decisions, we can improve prescribing and help prevent deaths from prescription opioid overdose.

Thank you to the many Pain News Network readers who took the time to share your thoughts with us. As we move forward, we will continue to look for opportunities to work with you on the critical issue of safer, effective pain management.

Debra Houry, MD, is a former emergency room physician and professor at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. In 2014, she was named director of the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Houry can be emailed at vjz7@cdc.gov and reached on Twitter at @DebHouryCDC.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.

For a look at the first draft of the CDC’s opioid prescribing guidelines, click here.