New Software Helps Doctors See Kids' Pain Levels

/By Pat Anson, Editor

Accurately assessing pain levels in a patient is difficult because pain is so subjective. No one really knows how much pain a patient is in – except the patient.

It gets even harder when the patient is a young child who can’t verbally express their feelings the same way an adult can. For decades doctors have relied on low-tech diagnostic tools like the Wong Baker Pain Scale – a series of sad and smiling faces the child chooses from to help the doctor understand how much pain they are in.

Thankfully, that era may be coming to an end with the development of a high-tech approach at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine.

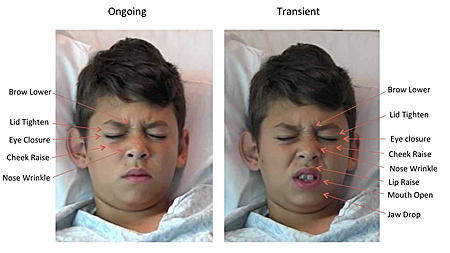

Researchers there have demonstrated the validity of new software that measures pediatric pain by recognizing facial patterns in each patient. Their study is published online in the journal Pediatrics.

“The current methods by which we analyze pain in kids are suboptimal,” said senior author Jeannie Huang, MD, a professor in the UC San Diego School of Medicine Department of Pediatrics and a gastroenterologist at Rady Children's Hospital-San Diego.

COURTESY UC SAN DIEGO SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

“In this study, we developed and tested a new instrument, which allowed us to automatically assess pain in children in a clinical setting. We believe this technology, which enables continuous pain monitoring, can lead to better and more timely pain management.”

The researchers used the software to analyze pain-related facial expressions from video taken of 50 youths, ages five to 18 years old, who had laparoscopic appendectomies.

Researchers filmed the patients during three different post-surgery visits: within 24 hours of their appendectomy; one calendar day after the first visit and at a follow-up visit two to four weeks after surgery. Facial video recordings and self-reported pain ratings by each patient, along with pain ratings by parents and nurses were collected.

“The software demonstrated good-to-excellent accuracy in assessing pain conditions,” said Huang. “Overall, this technology performed equivalent to parents and better than nurses. It also showed strong correlations with patient self-reported pain ratings.”

Huang says the software also did not demonstrate bias in pain assessment by ethnicity, race, gender, or age – an important consideration given how subjective current pain scales can be.

Because the software operates in real-time, doctors can be alerted to pain when it occurs instead of during scheduled assessments. The technology could also advocate for children when their parents are not around to notify medical staff about their child's pain level.

Huang said the software needs further study with more children and other types of pain in a clinical setting.

“It still needs to be determined whether such a tool can be easily integrated into clinical workflow and thus add benefit to current clinical pain assessment methods and ultimately treatment paradigms,” she said.

Huang says controlling pain is important, not only for the child's comfort, but also for their recovery since studies have shown that under-treatment of pain is associated with poor surgical outcomes.