FDA Warns About Fast Opioid Tapers

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued an unusual warning Tuesday cautioning doctors not to abruptly discontinue or rapidly taper patients on opioid pain medication.

The agency said in a statement it had received reports of “serious harm in patients who are physically dependent on opioid pain medicines suddenly having these medicines discontinued or the dose rapidly decreased.” The harm includes withdrawal symptoms, uncontrolled pain, psychological distress and suicide.

The FDA gave no details on cases of patient harm but said it was tracking them and would require changes on opioid warning labels to help instruct physicians on how to safely decrease opioid doses.

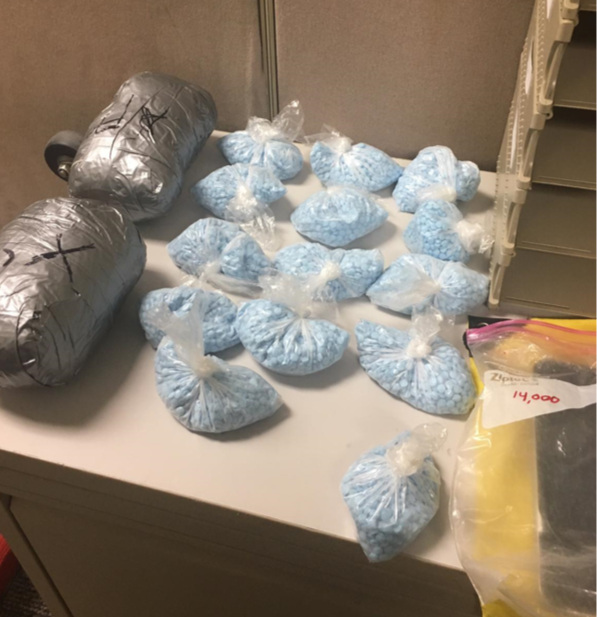

“Rapid discontinuation can result in uncontrolled pain or withdrawal symptoms. In turn, these symptoms can lead patients to seek other sources of opioid pain medicines, which may be confused with drug-seeking for abuse. Patients may attempt to treat their pain or withdrawal symptoms with illicit opioids, such as heroin, and other substances,” the FDA said.

In recent years, there have been an increasing number of anecdotal reports of pain patients committing suicide or turning to illegal drugs for pain relief. It is not clear why the FDA decided to act now, just days after the departure of former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD.

In PNN’s recent survey of nearly 6,000 patients, over 80 percent said they had been taken off opioids or had their dose reduced. Nearly half said they had considered suicide because their pain is poorly treated and many were turning to other substances – both legal and illegal – for pain relief.

11% obtained opioid medication from family, friends or black market

26% used medical marijuana for pain relief

20% used alcohol for pain relief

20% used kratom for pain relief

4% used illegal drugs (heroin, illicit fentanyl, etc.) for pain relief

Last December, over a hundred healthcare professionals warned in a joint letter to the Department of Health and Human Services that forced opioid tapering has led to “an alarming increase in reports of patient suffering and suicides” and called for an urgent review of tapering policies at every level of healthcare.

“This is a large-scale humanitarian issue,” the letter warns. “New and grave risks now exist because of forced opioid tapering.”

Federal agencies widely differ on opioid tapering recommendations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend a "go slow" approach, with a "reasonable starting point" being 10% of the original dose per week. Patients who have been on opioids for a long time should have even slower tapers of 10% a month, according to the CDC.

The Department of Veterans Affairs recommends a taper of 5% to 20% every four weeks, although in some cases the VA suggests an initial rapid taper of 20% to 50% a day “if needed.”

In its warning, the FDA cautioned doctors that no standard opioid tapering schedule exists that is suitable for all patients.

“When you and your patient have agreed to taper the dose of opioid analgesic, consider a variety of factors, including the dose of the drug, the duration of treatment, the type of pain being treated, and the physical and psychological attributes of the patient,” the FDA said. “Create a patient-specific plan to gradually taper the dose of the opioid and ensure ongoing monitoring and support, as needed, to avoid serious withdrawal symptoms, worsening of the patient’s pain, or psychological distress.”

The FDA urged patients and doctors to report side effects from opioid discontinuation and rapid tapers at druginfo@fda.hhs.gov or to call 855-543-DRUG (3784) and press 4.